A thing which you enjoyed and used as your own for a long time, whether property or opinion, takes root in your being and cannot be torn away without your resenting the act and trying to defend yourself, however you came by it.

—Oliver Wendell Holmes

Chances are you drive to work alone and park free when you get there. Ninety-one percent of commuters in the United States travel to work by automobile, 92 percent of commuters’ automobiles have only one occupant, and 94 percent of automobile commuters park free at work.

Employers provide 85 million free parking spaces for commuters. The resulting tax-exempt parking subsidies are worth $31.5 billion a year.

Employer-paid parking is the most common tax-exempt fringe benefit in the United States. Tax exemptions are usually justified on grounds that they promote a public policy, but employer-paid parking is a matching grant for driving to work: the employer pays part of the cost of commuting by car (the parking cost) only if the employee matches it by paying the rest of the cost (the driving cost). This matching-grant arrangement encourages solo driving to work.

California’s Parking Cash-Out Law

To reduce traffic congestion and air pollution,

California enacted a parking cash-out law in 1992. The law requires employers who subsidize parking to give commuters the option of receiving cash instead. The cash-out requirement applies only to parking spaces that an employer rents from a third party. Therefore, if a commuter trades a parking space for cash, the money previously devoted to renting a parking space becomes the commuter’s cash allowance. Giving commuters a choice between a parking subsidy and its value in cash reveals that free parking has a cost—the foregone cash. Commuters who forego the cash are, in effect, spending it on parking. The cash option converts employer-paid parking from a matching grant for driving to work into an unrestricted cash grant. Employers can continue to offer free parking, but the new option to take cash instead of parking should increase the share of commuters who walk, bicycle, or ride the bus to work.

California enacted a parking cash-out law in 1992. The law requires employers who subsidize parking to give commuters the option of receiving cash instead. The cash-out requirement applies only to parking spaces that an employer rents from a third party. Therefore, if a commuter trades a parking space for cash, the money previously devoted to renting a parking space becomes the commuter’s cash allowance. Giving commuters a choice between a parking subsidy and its value in cash reveals that free parking has a cost—the foregone cash. Commuters who forego the cash are, in effect, spending it on parking. The cash option converts employer-paid parking from a matching grant for driving to work into an unrestricted cash grant. Employers can continue to offer free parking, but the new option to take cash instead of parking should increase the share of commuters who walk, bicycle, or ride the bus to work.

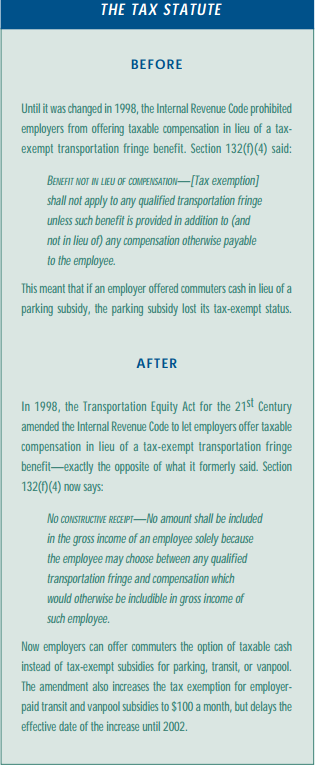

But there was a problem. Until 1998, the Internal Revenue Code imposed a tax penalty for cashing out parking subsidies. Section 132(f)(4) of the Code stated that employer-paid parking was taxable if “provided in addition to (and not in lieu of) any compensation otherwise payable to the employee.” This meant that if an employer offered commuters the option to choose cash instead of free parking, the free parking became taxable income.

Suppose that, to comply with California’s cash-out law, an employer offered carpoolers a cash subsidy equal to the parking subsidy they would receive if they drove to work alone. That is, suppose the employer broadened the offer from the choice between free parking and nothing to the choice between free parking and its cash value. If the employer offered this option, the free parking ceased to qualify as a tax-exempt transportation fringe benefit because it was no longer “provided in addition to (and not in lieu of) compensation otherwise payable to the employee.” If an employer complied with California’s cash-out law, commuters who did not cash out the free parking had to pay income tax on the formerly tax-exempt parking subsidy. This tax penalty discouraged employers from offering the cash option.

The not-in-lieu-of-compensation provision makes sense for fringe benefits that promote public purposes. For example, disallowing the choice between a pension contribution and cash compensation makes sense because pension contributions increase retirement income, which is desirable. But disallowing the choice between free parking and cash compensation does not make sense because free parking increases traffic congestion and air pollution, which are undesirable.

Cashing Out Does Reduce Traffic

In 1998, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) eliminated the not-in-lieu-of-compensation provision for transportation fringe benefits. As a result, employers can now offer commuters the option to choose taxable cash instead of tax-exempt parking, transit or vanpool subsidies. This minor amendment to the tax code will have major consequences for transportation and air quality. Employers in California have greater incentive to comply with the state’s cash-out law, and employers throughout the nation can finance a broad array of commuter travel choices with the same money they now spend to subsidize parking.

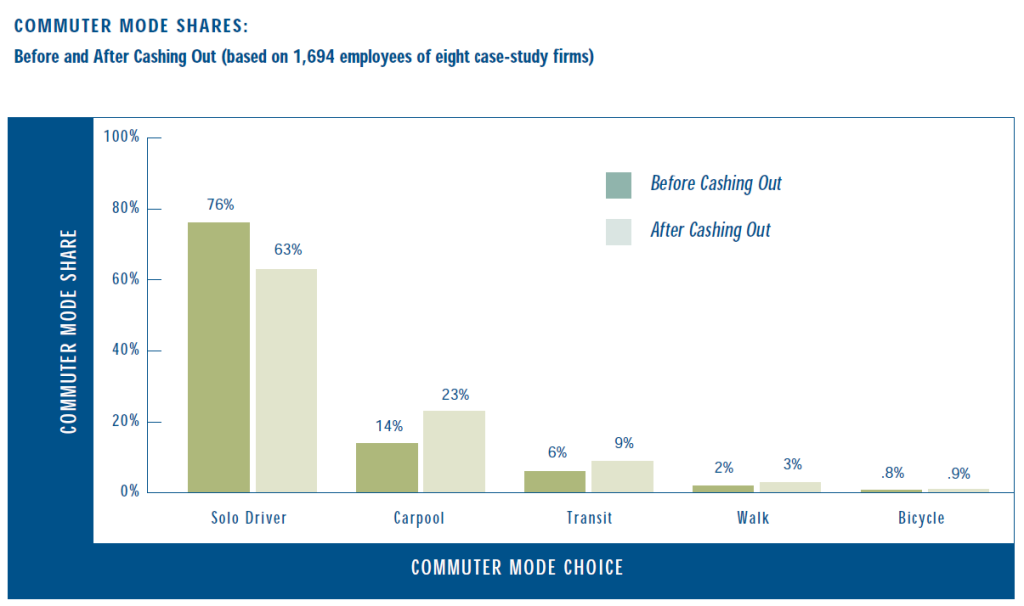

Cashing out employer-paid parking reduces traffic congestion and air pollution. Case studies of eight firms that have already complied with California’s cash-out law found that solo driving to work fell by 17 percent after cashing out. The solo-driver share for commuting to the eight firms fell from 76 percent before the cash offer to 63 percent afterward. For every 100 commuters offered the cash option, thirteen solo drivers shifted to another travel mode. Of these thirteen former solo drivers, nine joined carpools, three began to ride transit, and one began to walk or bicycle to work. Because of these shifts, vehicle-miles traveled and vehicle emissions for commuting to the eight firms fell by 12 percent.

The large shifts from solo driving to ridesharing came at almost no cost to employers. The cash payments are a more flexible use of funds previously dedicated to subsidizing parking. The eight firms, considered together, reduced their parking subsidies by almost as much as they increased their cash payments in lieu of parking subsidies. The average commuting subsidy per employee rose from $72 to $74 a month, or by only 3 percent.

Beyond reducing traffic congestion and air pollution, cashing out employer-paid parking will also increase tax revenues without increasing tax rates. Suppose an employer pays $100 per space per month to provide free parking. A commuter in the 25-percent marginal tax bracket who chooses a taxable $100 payment instead of the free parking will receive $75 after tax. The $25 in added tax revenue results from voluntary action: a commuter chooses $75 in after-tax cash rather than a parking space that costs $100 to provide. This revenue windfall comes from reducing the inefficiency that occurs when, faced with the typical choice between free parking and nothing, commuters take parking spaces they value at less than what the employer pays to provide them.

In the eight case studies of firms that offer parking cash out, employees’ taxable wages increased by $255 per year per employee offered the cash option. The federal government assumes a 19-percent marginal tax rate to calculate the effects of changes in taxable wage income, and California assumes a 6.5-percent marginal tax rate. At these tax rates, federal income tax revenues increased by $48 per employee per year, and California income tax revenues increased by $17 per employee per year. Therefore, federal and state tax revenues increased by $65 per year per employee offered the cash option.

Cashing Into Tax-Exempt Parking

The Internal Revenue Code amendment allows commuters to cash out tax-exempt parking—and also allows other commuters to cash into tax-exempt parking. Without increasing employees’ total compensation, employers who do not subsidize parking can now offer tax-exempt parking to commuters who agree to accept a compensating reduction in their taxable wages. Because tax-exempt parking can be offered in lieu of taxable cash income, commuters can pay for parking at work with pre-tax income.

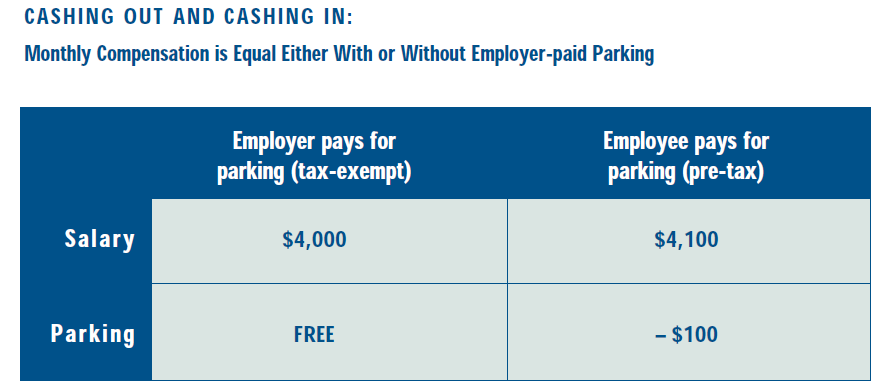

For example, suppose a commuter whose employer does not subsidize parking earns a salary of $4,100 a month and pays $100 a month for parking at work. The employer can now offer this commuter the option to choose either a salary of $4,100 a month without parking or a salary of $4,000 a month with parking. If the commuter takes the parking, the commuter’s pre-tax income declines by $100 a month. Both the commuter and the employer save payroll taxes on the $100-a-month reduction in taxable wages, and the commuter also saves income taxes on the same $100 a month.

If employers adjust cash wages to compensate for differences in fringe benefits, the tax consequences are the same whether the employer or the employee pays for parking. The cash foregone by a commuter who parks at work will be the same whether or not the employer offers “free” parking. A commuter who earns $4,000 a month with employer-paid parking that can be cashed out for $100 a month in taxable income receives the same compensation as a commuter who earns $4,100 a month without employer-paid parking and pays $100 a month (pre-tax) to park In both cases the commuter can take either $4,000 in taxable wages with a- parking space or $4,100 in taxable wages without a parking space. In both cases the commuter’s cost of parking is the after-tax value of $100 a month.

This example is not merely hypothetical. The University of California has arranged for employees’ payroll deductions for parking to be taken from pre-tax income, up to the tax-exempt limit of $175 a month for employer-paid parking. As an employer, the University will save an estimated $1 million a year in Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes from this arrangement. The University’s employees will save an estimated$5.4 million a year in Social Security, Medicare, and federal income taxes (see Table). The tax savings per employee range from $69 a year at UC Santa Barbara to $236 a year at UCLA. The higher tax savings at UCLA reflect the higher prices for parking at UCLA.

Commuter-paid parking is not automatically tax exempt. That is, commuters can pay for parking at work out of pre-tax income only if their employers allow them to take parking in exchange for a reduction in taxable income. Therefore, the tax-exemption for commuter-paid parking is due to a voluntary reduction in taxable income.

Despite the tax revenue lost when unsubsidized commuters cash into tax-exempt parking, Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that cashing out tax-exempt parking and cashing into it will increase federal income tax and Social Security tax revenues by $169 million between 1998 and 2007. This estimated net revenue windfall for the federal government is (1) the increase in tax revenue from commuters who cash out their tax-exempt parking and pay taxes on the cash, minus (2) the decrease in tax revenue from commuters who cash into tax-exempt parking and avoid taxes on the parking. The $169 million increase in federal tax revenue is the net change from all commuters who make a trade between tax-exempt parking and taxable cash, in either direction. Because many more commuters can cash out of tax-exempt parking than can cash into it, the federal government gains more tax revenue than it loses.

The reduced after-tax price of parking for those who do not already park free at work will presumably induce some commuters to begin driving to work. But 91 percent of commuters drive to work, and 94 percent of automobile commuters park free at work, so relatively few commuters can begin driving to work. For these commuters, paying for parking with pre-tax income reduces the price of parking by the commuter’s marginal tax rate. In comparison, the option to cash out free parking will increase the opportunity cost of taking the parking from nothing to the after-tax value of the parking subsidy. Therefore, the option to cash in will reduce the price of parking by 20 to 30 percent for a few commuters, and the option to cash out will increase the price of parking by 70 to 80 percent for many commuters.

Equity

Cashing out and cashing in will increase transportation and tax equity in three ways. First, cashing out will improve equity among commuters who are offered free parking. Without the cash option, free parking provides no benefit to commuters who walk, ride their bikes, or take transit to work. With the cash option, employers can easily offer the same transportation benefit to all commuters.

Second, cashing out and cashing in will improve equity between commuters who park free and commuters who pay to park. If commuters who park free can cash out, and commuters who pay to park can cash in, everyone can pay for parking with pre-tax income. The opportunity cost of taking a parking space at work will be the same whether or not the employer subsidizes parking.

Second, cashing out and cashing in will improve equity between commuters who park free and commuters who pay to park. If commuters who park free can cash out, and commuters who pay to park can cash in, everyone can pay for parking with pre-tax income. The opportunity cost of taking a parking space at work will be the same whether or not the employer subsidizes parking.

Third, cashing in will enable many transit and vanpool commuters to pay their commuting expenses with pre-tax income. Most automobile commuters now receive tax-exempt free parking while most transit and vanpool commuters pay with taxable income. Pre-tax payment for transit and vanpools can remove the inequity.

Conclusion

The tax exemption for employer-paid parking is an anomaly among tax-exempt fringe benefits because it stimulates behavior that other public policies are designed to discourage—solo driving to work. TEA-21 amended the Internal Revenue Code to give commuters the option to choose cash in lieu of any parking subsidy offered. The amendment allows the 94 percent of commuters who park free at work to cash out their employer-paid parking subsidies. The amendment also benefits a small group of people the tax code had previously discriminated against because the 6 percent of automobile commuters who pay for parking can now pay with pre-tax income. Transit and vanpool commuters can also pay their commuting cost with pre-tax income.

The tax code continues to favor solo driving to work because parking subsidies remain tax exempt and cash is taxable. Therefore, allowing commuters to take taxable cash in lieu of a tax-exempt parking subsidy is a small reform. But as Justice Ginsberg, quoting Justice Cardozo, recommended in her Senate confirmation hearing, “Justice is not to be taken by storm. She is to be wooed by slow advances.”

Further Readings

Donald Shoup, Cashing Out Employer-Paid Parking (Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation, 1992).

Donald C. Shoup and Richard W. Willson, “Employer-Paid Parking: The Problem and Proposed Solutions,” Transportation Quarterly, April 1992, pp. 169-192.

Donald C. Shoup, Evaluating the Effects of Parking Cash Out: Eight Case Studies (Sacramento: California Environmental Protection Agency, 1997).

Donald C. Shoup, “Evaluating the Effects of Cashing Out Employer-Paid Parking: Eight Case Studies,” Transport Policy, vol. 4, no. 4, October 1997, pp. 201-216.