I am a transportation researcher and a landscape painter, two activities that couldn’t seem more different. But are they? Transportation models are an abstraction from reality. Painting, even representational painting, requires abstraction from an infinitely complex visual field. Both types of abstraction require decisions about what is in and what is excluded. So perhaps transportation research and painting have more in common than we might think. Furthermore, do transportation paintings provide insights that transportation research excludes?

The abstraction required for research creates a separation from the richness of individuals’ thoughts, feelings, and internal narratives. If travel patterns evolved slowly, this might not be such a problem. But lately that is not the case: travel is being rapidly altered by changes in technology, environment, and culture. A deep, qualitative understanding of travel has never been more important.

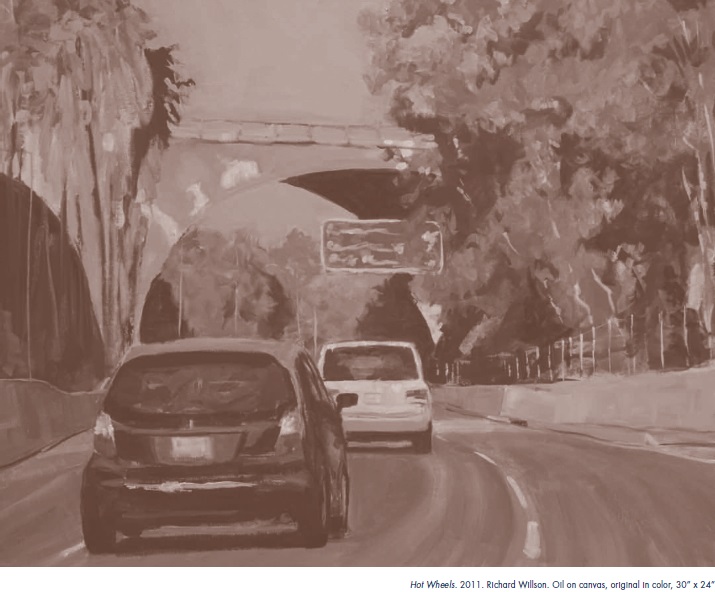

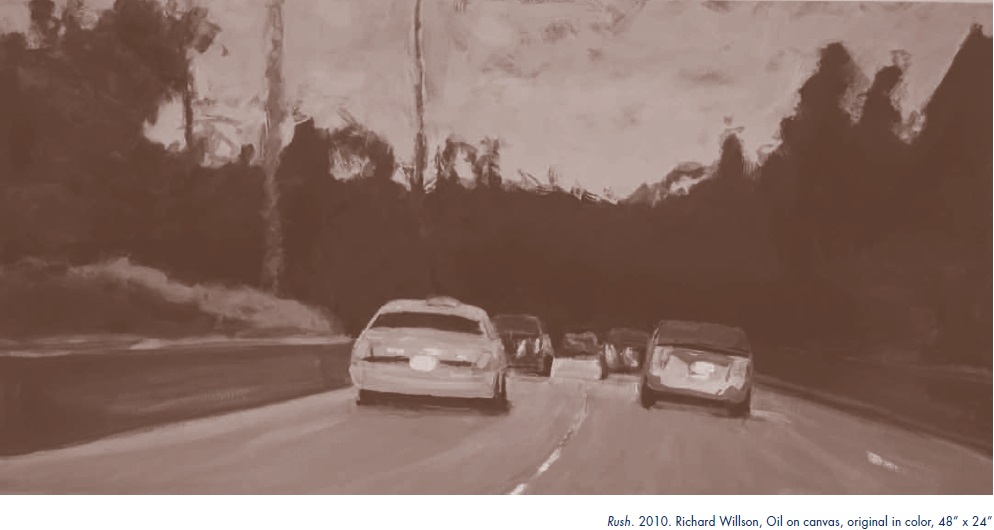

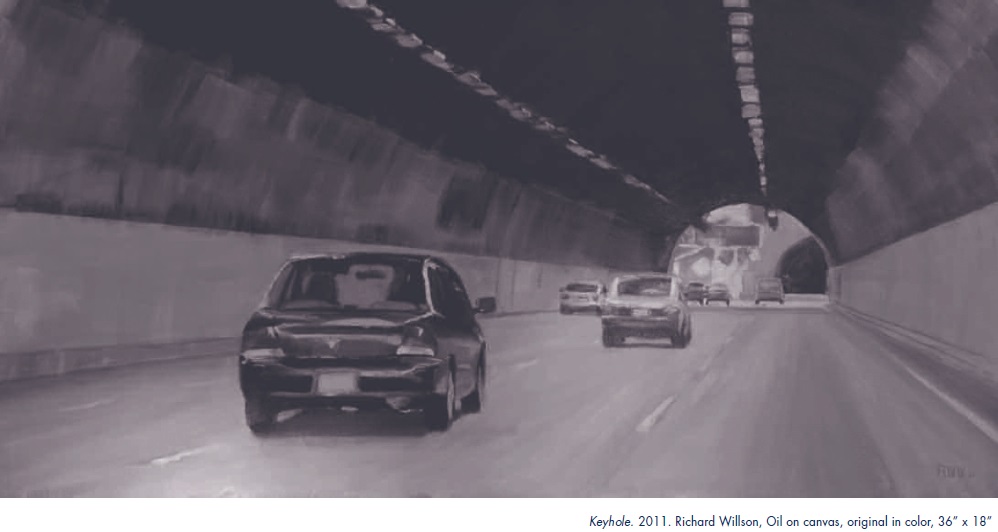

As a painter, I spend a lot of time observing and rendering transportation facilities. The freeway views displayed in this article are studio paintings, as Caltrans would not close the freeway for my usual “en plein air” (open air) style. The subject is the iconic 110 Freeway in Southern California; the perspective is the visual field of the driver. When on display, the paintings evoke reactions that provide insights into how people feel about their travel. A typical response is that there is not enough traffic shown, which when stated, is usually followed by a wink that suggests I understand the grim reality of traffic. Viewers express a desire for speed but share their horror of those who drive too fast. They yearn for the “good old, uncongested days” but have a false picture of prior conditions. Reactions are also tied to experiences of the freeway in specific times and places such as being “almost home” or “past a bottleneck.”

When I showed the paintings in South Pasadena—a small city whose residents are working to block the extension of the 710 Freeway—some viewers suggested that I didn’t make the freeway ugly enough. They didn’t want to acknowledge any pleasure in the freeway experience. “Are the paintings a celebration of freeways or an indictment?” “Are you [the artist] for or against freeways?” Contradictory emotions were on display: high expectations for personal mobility alongside unwillingness to accept local disruption. These complex tensions reveal the inadequacy of relying on economic data or simple attitudinal survey questions for transportation knowledge.

Creating the paintings has helped me understand three aesthetic forms that are part of the freeway experience.

First, the windshield of the vehicle frames an aesthetic of the visual landscape. The dimensions of the window frame replicate a movie screen or flat screen television. When driving, we create our own movie, complete with streaming visuals and an internal narration. While the world beyond the window is three dimensional, the frame suggests a two-dimensional world. In this way, the driving experience is a transition from the immersive experience of a person on foot, to the detached, two-dimensional experience of human-made virtual worlds. Drivers are separated from a three-dimensional reality by a glass curtain. They observe the beauty and ugliness of the city from a command position, protected from intrusions into their personal space. They are looking forward, down the road, with the agency that comes with control. This contrasts with the experience of transit riders, walkers, and cyclists, who are either looking out the side window of a transit vehicle or are engaged by the urban environment.

There is beauty in the infrastructure itself, of course, as seen in soaring freeway interchanges and ribbons of concrete reflective of the underlying topography. Drivers experience the power of human ingenuity. The desire for order is fulfilled in the networks, systems, hierarchy, and uninterrupted continuity of freeways. Freeways provide hard edges and boundaries that telegraph human organization of the natural environment. But they also show the sky, flora, and fauna that flow by in changing seasons. How many people have experienced an amazing sunset alone in their vehicle, and how did driving affect their perception of the scene?

Second, freeway travel evokes an aesthetic of driving. This is an essential part of the driver’s experience, not available in other modes. Freeway driving means power: mastery of fire that overcomes inertia when mashing the gas pedal down. There is pleasure in acceleration and the masterful handling of the vehicle, sensing coefficients of friction, managing weight transfer, and finding the apex of a turn. And of course, a vehicle can be an instrument for dominating other drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians.

Third, freeway driving reveals an aesthetic of cooperation. While media attention focuses on driver discourtesy, competition, and road rage, clear-eyed observation of driver behavior reveals that cooperation and courtesy dominate the experience. Without enforcement present, drivers let others merge into their lanes, take turns merging, pull over to assist others, and move out of the passing lane if driving slowly. The freeway system could not function without this cooperation. Drivers participate in a dance, generating a communal choreography as they go. Of course there are exceptions, but courtesy and altruism rule the day.

The experience of painting these freeways taught me to observe carefully and avoid jumping to conclusions, just as I should in research. It made me think about the people in the vehicles, and wonder about their experience. While transportation facilities are fixed, their use depends on subjective human beings. More fundamentally, even though my research seeks to reduce automobile dependency, I became aware of how much appreciation and fondness for freeways I was bringing to the paintings—these wondrous but flawed human achievements.

I was painting a nostalgic farewell to a time never to return. The modernist vision of free flowing freeways is over. Communication replaces movement and the virtual challenges the real. Extreme congestion undoes the driver’s feeling of control and agency. Technological driving assistance and autonomous vehicles undermine the idea of the driver as the commander of the enterprise. Electric vehicles eliminate the “mastery of fire” feeling. Many young adults have never experienced driving down a freeway, and they do not seek it. They don’t own cars. They live in the three-dimensional world on foot, on bicycles, and in transit vehicles. Automakers know this—they are branching into mobility services. Application developers know this—they are developing services that render the reasons to own a personal vehicle moot. This is truly a sea change. Do transportation researchers know this?

Transportation paintings do not solve the research challenges of this new era. Neither do they overcome the distance between research and individual subjectivity. Painting transportation facilities does, however, invite me to observe and reflect. It makes me more open to understanding change. And if the paintings are doing their work, they lead viewers to consider the less tangible aspects of travel, and their own choices.

Further Readings

Richard Willson’s Paintings: http://richard-willson.artistwebsites.com

Richard Willson Painting and Poetry: https://www.facebook.com/rwwpaintingandpoems