Streets are more than public utilities, more than mere traffic conduits, more than the equivalent of water lines and sewers and electric cables, more than linear physical spaces that permit people and goods to get from here to there. To be sure, communication remains a major purpose, along with unfettered public access to property. These roles have received abundant attention, particularly in the latter half of the twentieth century. Other roles have not.

Streets shape the form and comfort of urban communities. Their sizes and arrangements give or deny light and shade. They may focus attention and activities on one or many centers, at the edges, along a line, or they may simply direct one’s attention to nothing in particular. The three streets that lead from the Piazza del Popolo in Rome, Via del Corso in the center, give focus to that city as does nothing else. So does Market Street in San Francisco and a hundred Main Streets in small cities across the United States.

Streets allow people to be outdoors. Except for private gardens, which many urban people do not have or want, or immediate access to countryside or parks, streets constitute the out-of doors for many urbanites. Streets are also places of social and commercial encounter and exchange. They are where people meet-which is a basic reason we have cities in any case. People who really do not like other people, not even to see them in any numbers, have good reason not to live in cities or to live isolated from city streets.

The street is movement – to watch, to pass – especially movement of people: of fleeting faces and forms, changing postures and dress. You see people ahead of you or over your shoulder or not at all, absorbed in whatever has taken hold of you for the moment, but aware and comforted by the presence of others all the same. You can stand in one place or sit and watch the show. The show is not always pleasant, not always smiles or greetings or lovers hand-in-hand. There are cripples and beggars and people with abnormalities, and, like the lovers, they can give pause: they are cause for reflection and thought. Everyone can use the street. Being on the street and seeing people, it is possible to meet them, ones you know or new ones. Knowing the rhythm of a street is to know who may be on it, or at a certain place along it during a given period; knowing who can be seen there or avoided.

As well as to see, the street is a place to be seen. Sociability is a large reason cities exist, and streets are a major if not the only public place for that sociability to develop. At the same time, the street is a place to be alone, to be private. It’s a place where the mind can wander, triggered by something there on the street, or by something internal, more personal. It’s a place to walk while whatever is inside unfolds.

Some streets are for exchange of services or goods: places to do business. They are public showcases, meant to exhibit what a society has to offer, and to entice. The merchant offers the goods, displays them, on the street if allowed, with wares to be seen. The looker sees, compares, fingers, discusses with a  companion, and ultimately decides whether to enter the selling environment or not, whether to leave the anonymity and protection of the public realm and enter into private exchange.

companion, and ultimately decides whether to enter the selling environment or not, whether to leave the anonymity and protection of the public realm and enter into private exchange.

The street is a political space. It’s on Elm Street that neighbors discuss zoning or impending national initiatives and on Main Street, at the Fourth of July parade as well as the anti-nuclear march, that political celebrations take place. It’s not easy to distribute non-mainstream ideas in a shopping mall, much less to have a demonstration in one. Those are private places. Lest we discount the importance of the public street as a political place in favor of modern electronic media of communication, recall where the demonstrations and actions and marches of the late 1980s took place in Eastern Europe: in public places and most especially in streets.

It is not surprising that, given their multiple roles in urban life, streets require and use vast amounts of land. In the United States, from 25 to 35 percent of a city’s developed land is likely to be in public rights-of-way, mostly in streets. When we speak of the public realm, we are speaking in large measure of streets. What is more, streets change. They are tinkered with constantly. Every change opens an opportunity for improvement. If we can develop and design streets so that they are wonderful, fulfilling places to be – community-building places, attractive public places for all people – then we will have successfully designed about one-third of the city directly and will have had an immense impact on the rest.

So, in our pursuit of good and fulfilling urban places, it is important to study the physical, designable, buildable qualities of the best streets – the great streets.

AMERICA’S RESIDENTIAL BOULEVARDS

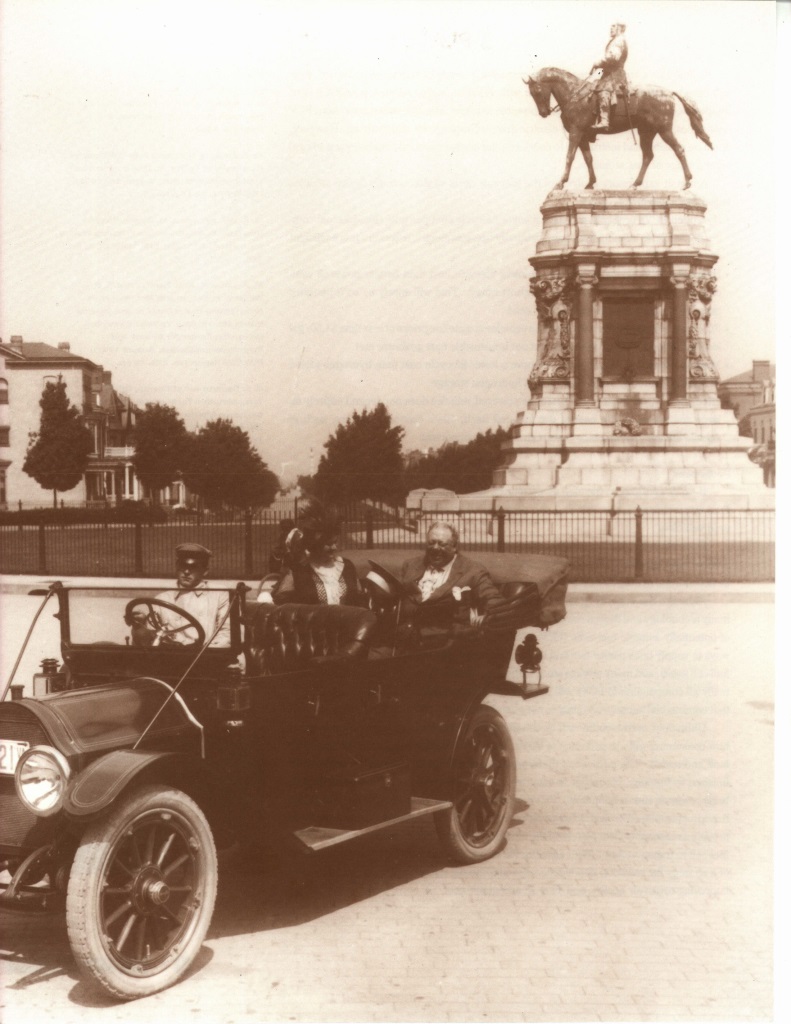

The residential boulevard may be a unique North American contribution to the world’s streets. Generally wide, residential boulevards are invariably tree-lined, they often have graceful curves, they are shaded and cool in the summer, and they are quiet. They come with or without a planted median (through which a trolley may once have run) and they are long. Lined with large homes, spaced at some distance from each other and well set back from the street on cared-for lawns, these streets bespeak well-being. They were supposed to. Often they were the centerpiece of land development promotions and were finely built in advance of the homes that were to line them, to give a sense of what was to come, to tell the prospective well-to-do owner-builder that this would be just the place for him and his family. Roots of these streets may be in French boulevards, or English villages, or the residential sections of earlier American small towns with their elm-shaded main streets. They are often associated with suburban development, not as often with central urban environments.

The various parkways connecting the lakes and that are part of the Minneapolis park system are such streets, and so is Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, D.C., Shaker Boulevard in Shaker Heights, Ohio, and Fairmount Boulevard or Euclid Heights Boulevard in Cleveland Heights, immediately east of Cleveland. Still others are Saint Charles Avenue in New Orleans (an urban example) and Orange Grove Boulevard in Pasadena, California. Monument Avenue is urban and not far from the city center. Nor is it necessary to be well-to-do to live along it. Its physical design is compelling.

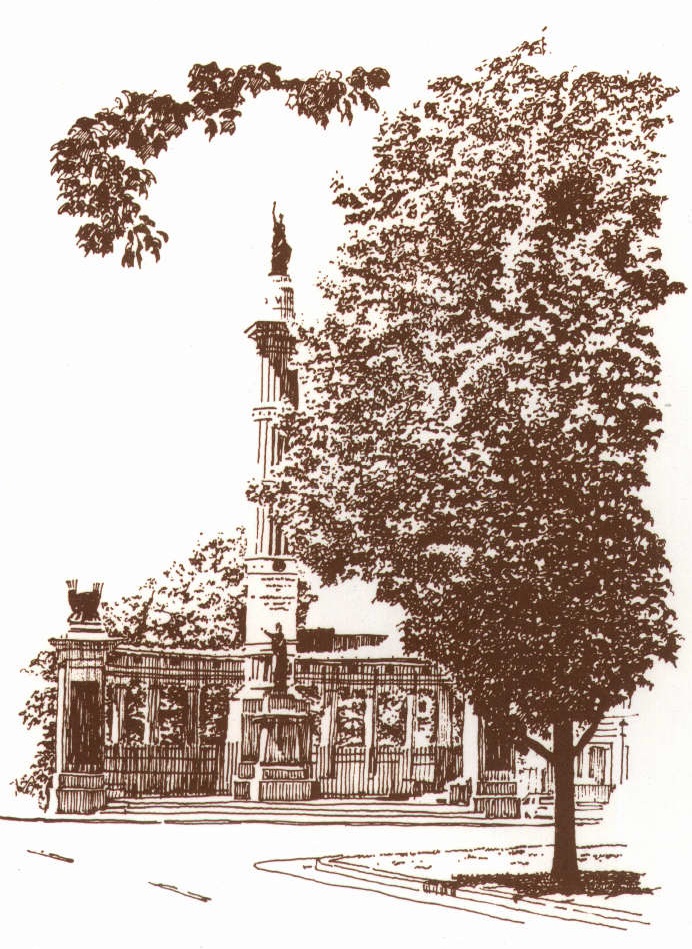

MONUMENT AVENUE

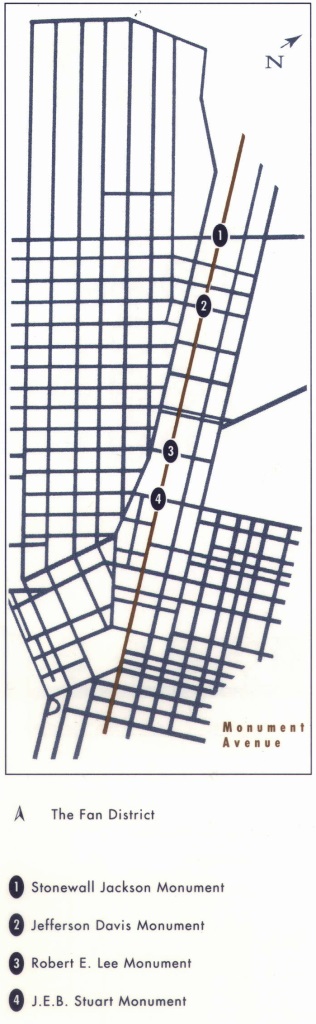

Monument Avenue starts with a different name, Franklin Street, at Capitol Square in the downtown area, one and one-half miles away, and becomes Monument Avenue at Stuart Circle, marked by a statue of “Jeb” Stuart. It then proceeds straight in a northwesterly direction for many miles to the end of the city. At its officially named beginning, Monument Avenue is part of the Fan District, two blocks in from this area’s northern edge.

The Fan District is made of tight urban streets lined with mostly brick townhouses that share common walls, and with one-, two-, and four- family dwelling structures and apartment buildings set close to each other and narrowly setback from the sidewalks. Along some streets there is a sense of elegance and of early wealth. Just to the east of the Fan District lies Virginia Commonwealth University – many new buildings mixed with old ones, students, growth, activity, some spilling over into the Fan. It is the kind of area that, during the 1950s and 1960s, was classified as “inner city blight.” Still, people who saw the potential of the location, the urban streets, and the housing, devoted great care to the Fan District. There has been much restoration, often, it seems, by young people. Not all of the Fan District is in the best condition; if there was wealth earlier, some of it seems gone now, but the elegance and the urbanity remain.

We are interested in the stretch of Monument Avenue running from Stuart Circle to North Boulevard, a distance of eight blocks covering close to one mile. This section is a great street: an urban residential boulevard close to the city center; a grand remembrance to a lost cause, the Civil War. It is a positive achievement of physical design that is a social achievement as well.

The special character of the buildings along Monument Avenue lies more in their variations than in their individual designs. Some are outstanding and all are pleasant. They all have doors that face the street. They all have many windows, usually with fine panes, and many have porches that permit people to inhabit the street without actually being on it. Bricks are in a wide variety of earth tones. The 10 or 20 feet of front yard, a transition between public and private realms, permit a variety of landscape designs, including trees and flowering plants. Monument Avenue is not a street for one class of people: the elderly, young, and middle-aged live there, and the well-to-do and the less well-to-do, if not the indigent. There are not too many well-designed residential boulevards that can respond to the housing needs of a diverse population.

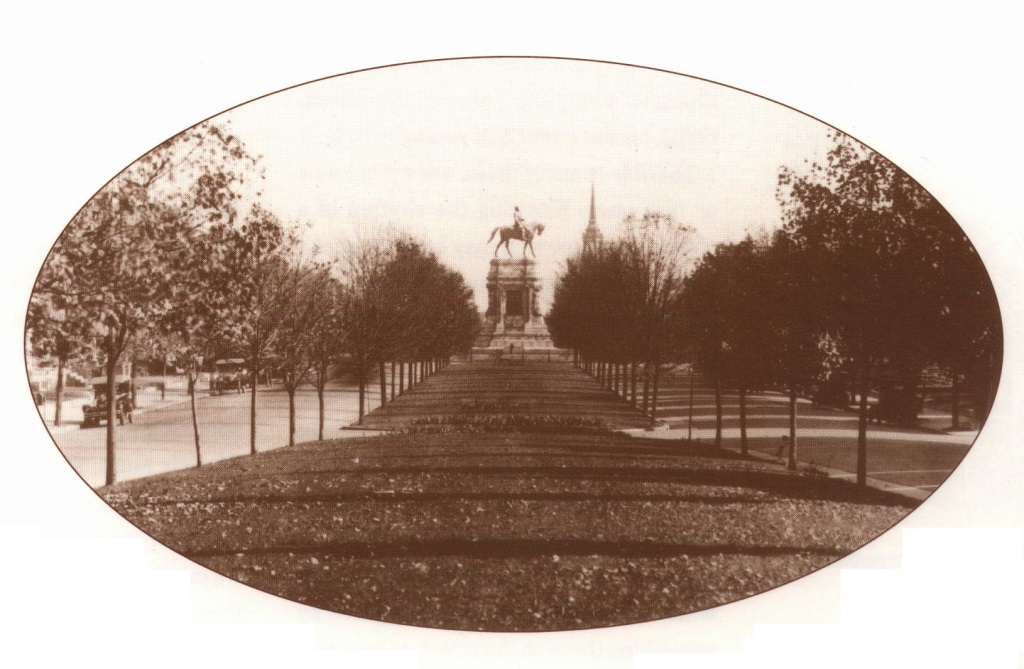

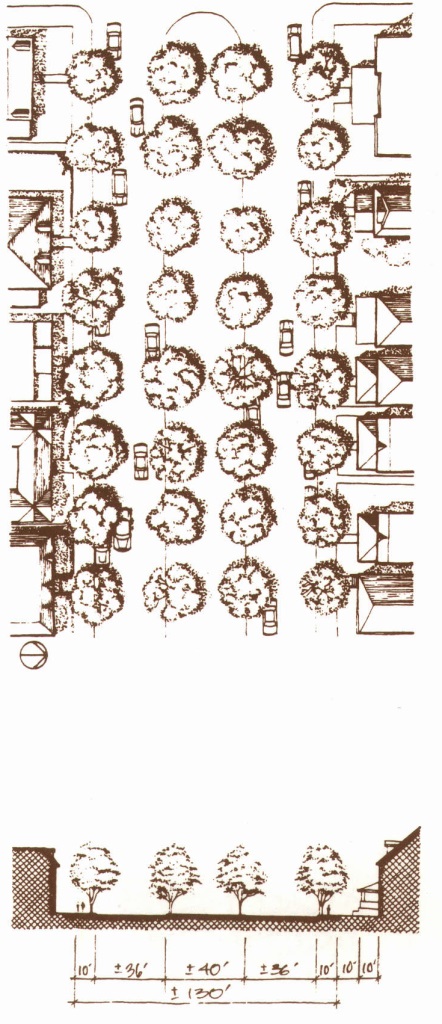

Monument Avenue’s street section is deceptively simple. A 40-foot central median is flanked by two 36-foot roadways which in turn are bounded by 10- foot sidewalks. Houses and small apartment blocks are set back 20 feet from the walks, except that porches, where they exist, are only 10 feet back. Buildings are two and one-half to three and one-half stories high. Just inside the curbs, along the two walks and in the median, are pin oaks and sugar maples, mostly the latter. Varying in height from 30 to 50 feet, they form four straight lines.

The linearity of extremely well-executed parts – the trees, the median, the streetlights, details of the curbs and street paving itself, and the houses – punctuated by four monuments along the way, accounts for the special physical character of the street. The tree spacing is uniform, 36 to 40 feet apart, and the trees line up across the street, coming as close as possible to intersections. Their crowns often join together, reinforcing the four lines. Streetlights spaced 80 to 115 feet apart also create lines along the sidewalks. The streetlights have two designs, with the most elegant being an acorn globe on a dark green, fluted pole. The two 36-foot-wide automobile roadways are paved with a gray asphalt brick bordered on each side by 3-foot wide concrete strips. Each roadway permits two parking lanes and two moving lanes, more (by one parking lane) than is permitted on a street of that width designed in the early 1990s. Since there are no breaks in the curbs, linearity is again emphasized. Finally, there are the buildings. Although they are different one from another in design and in materials (though many are brick), they are of similar height so that they, too, form lines along the street. They are close enough to each other that, walking or driving along the street, one does not normally see rear yards.

The linearity is punctuated on Monument Avenue. In addition to the focal points at the start and end of the street, monuments of Stuart at the start and of Stonewall Jackson at North Boulevard, there is the grandly scaled Lee Monument and the one of Jefferson Davis as well. Each is a focal point, each a reason to pause if not to stop. In the length of a mile, these special moments are important as reminders that we are on a marked, special path and we know when we have passed it. Traffic on this section of Monument Avenue moves purposefully but not with great speed. For reasons· not altogether understood – perhaps it’s the monuments that compel some attention,

perhaps it’s just the pleasantness of the drive and the not overly wide roadway-drivers seem to proceed reasonably, not speeding.

On a Sunday morning in spring, the trees have already bloomed. It is quiet, but there are people using Monument Avenue: churchgoers, joggers, cyclists, walkers. People who look like university students enter and leave apartment units.

Older women, at windows, watch the passersby. At various corners there are some small notices, and maybe a balloon or two. It seems that this is a route of a charity walk of some kind today. In small groups of ten to twenty, people are walking on this part of Monument Avenue, having come off one or two of the intersecting streets. In time one notices that groups are walking in both directions. There are people of all ages, blacks as well as whites in the same group. They pass along for several hours. There must have been good reasons for choosing Monument Avenue for their stroll. Without knowing for sure, one would like to think that it represents to the larger community a special place, a most pleasant street on which to be.

Interestingly enough, many of the best streets can and do handle a lot of auto traffic. But, the auto isn’t given priority over the other objectives and purposes. Often, these streets are not wide by today’s standards. Where they are, and certainly the right-of-way (but not the auto cartways) of Monument Avenue is wide, there are many non-traffic things in them – sidewalks, trees that continue to the corners, medians, details – that reduce the sense of largeness. In the end, it may be easier to design a great street, one that fits into a community, if multiple objectives are served than if we try to serve only one or two, especially if the one or two are traffic.

This article is adapted, with permission, from Allan B. Jacobs’ published book, Great Streets (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993).