A prevailing myth holds that America, land of plenty, provides everyone with vast opportunities for education, mobility, and food. Yet, not everyone shares this bounty. Significant sections of the population lack a neighborhood supermarket and thus end up paying high prices for inadequate or poor-quality food. Many of them do not have cars and thus depend on a transit system that fails to provide convenient access to groceries.

Adequate nutrition is commonly seen as a social welfare issue unrelated to transportation. So transportation planners have largely ignored the special needs of transit-dependent persons to access food, thus contributing to a critical problem.

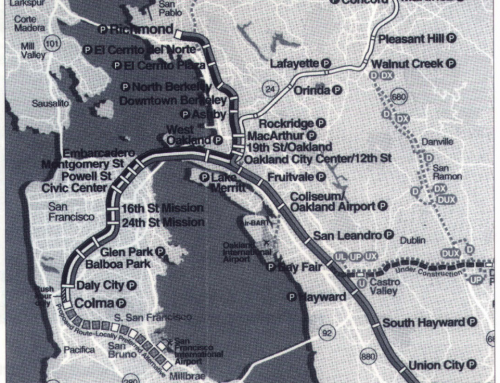

An effective transportation system does more than simply provide safe roads for automobiles. It affects people’s standards of living by facilitating access to jobs, stores, schools, parks, airports, and other desired destinations. Without the means to travel – whether by private vehicle or by transit – people cannot enjoy the most basic opportunities and resources, including the simple convenience of shopping at a supermarket or at a farmers’ market.

Lack of Inner-City Supermarkets

Between the 1960s and 1980s, there was a mass exodus of supermarkets from the inner city to the suburbs. This trend followed the ubiquitous outmigration of the middle-class and changes in the retail food industry that triggered intense competition for new markets. In Los Angeles the number of chain markets in inner-city locations shrank from forty-four in 1975 to thirty-one in 1991.

The University of Connecticut’s Food Policy Marketing Center conducted a major study of twenty-one metropolitan areas and found that nineteen of them had 30 percent fewer stores per capita in their lowest-income zip-code areas than regionwide averages. At the same time, the zip-coded areas with the fewest supermarkets per capita also had the lowest ratios of vehicle ownership.

Further, a USDA study found that only 22 percent of food-stamp recipients drove their own cars to purchase groceries, compared with 96 percent of non-food-stamp recipients – quite an extraordinary contrast, considering that non-food-stamp recipients enjoy much greater access to grocery outlets.

Adequate nutrition is commonly seen as a social welfare issue unrelated to transportation.

Recently some food chains have expressed modest interest in relocating to low-income urban communities, but transportation programs to improve access are still scarce among both food retailers and transit agencies. Some food suppliers, however, now recognize that providing transportation services for customers may further their own interests.

One compelling inducement for providing customer transportation is to reduce the rate of shopping-cart loss in areas with lower than average auto ownership. Grocers incur considerable hidden costs from cart theft or carts abandoned off site that require retrieval. The purchase of a new cart can cost as much as $120, and cart-retrieval expenses may amount to thousands of dollars each year for some stores in transit-dependent areas. At some sites, retrieved or stolen carts may account for as much as 10 percent of the store’s carts in a given year. The California Grocer’s Association estimates that 750,000 carts are taken annually from stores in California alone, creating theft and retrieval losses estimated at $17 million a year. To deter further cart loss, a few stores are beginning to explore transportation initiatives as an alternative to having customers walk home with their groceries in store-owned carts.

Food Stores As Transportation Suppliers

Despite supermarkets’ general lack of interest in providing customer transportation, a few food-store managers have initiated programs with an eye toward promoting goodwill and community service. Other programs have emerged through efforts of private retailers, public transit agencies, community groups, and nonprofit civic organizations. They include a variety of store-initiated van services, public transit programs, senior citizen transport programs, and food-delivery programs. Among these, three types of approaches appear feasible and promising.

First, supermarkets can establish private van services. In doing so they will likely realize profits not acknowledged by traditional accounting methods, such as through reduced shopping-cart loss, enhanced goodwill, increased customer loyalty, higher sales, less parking lot use, and possible regulatory relief from municipal ordinances such as shopping cart impoundment laws that charge fees for shopping carts left abandoned on city streets.

One example of this type of program is the Fine’s Market van service in East IA, which transports customers to and from the store. As a sign of its popularity, loyal Fine’s shoppers, appreciative of the store’s community orientation, created a human barricade around the store to prevent it from going up in flames during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

Second, joint ventures among private retailers, public entities, and community development organizations can establish transportation services to food outlets. The most prominent example of this strategy is the highly regarded Pathmark/New Communities Corporation (NCC) joint venture in Newark, New Jersey.

NCC is a community development corporation formed after the 1967 Newark riots. One of its earliest and most important objectives was to develop a supermarket-anchored shopping center in a low-income neighborhood that had been without a full-service market since the riots. After a lengthy process it forged an agreement with Pathmark’s parent corporation and established a 44,000-square-foot supermarket run by Pathmark. NCC holds a two-thirds interest in the venture plus ownership of the shopping center property.

As part of the venture, NCC extended its existing senior citizen van service, which takes seniors from NCC-owned housing to stores in Newark, thus creating a supermarket van service. Both the van service (which subsidizes other NCC programs) and the supermarket (which has the highest sales per square foot of all the Pathmark stores) have become highly profitable.

Third, nonprofits can engender substantial community participation in food transportation programs – a prerequisite for most paratransit and public transit services for the transit-dependent. One of the more innovative nonprofit ventures comes from an initiative by the Southland Farmers’ Market Association and the UCLA Community Food Security Project. Together, in October 1995, they created a “market basket” subscription program through the Gardena Farmers’ Market – one of the oldest markets in Southwest Los Angeles, serving primarily low- and middle-income neighborhoods. Those participating in the program receive a basket of “fresh from the farm” produce that is assembled at the Gardena market and then brought to a series of drop-off sites where they can be picked up. To encourage low-income participation, baskets are available at a less-expensive rate that is highly competitive with supermarket prices.

By establishing the program as a nonprofit community effort to increase food self-reliance, project organizers have made connections with key community players who are essential for its success.

Even with the drop-off point, project organizers have realized the critical lack of transportation services, both to deliver baskets to subscribers and to transport shoppers to the farmers’ market. To accomplish those goals, nonprofit groups are seeking to develop a delivery service to bring the baskets to people’s homes and a related service to transport shoppers to the farmers’ market. By establishing the program as a nonprofit community effort to increase food self-reliance, project organizers have made connections with key community players who are essential for its success.

These approaches must be developed in conjunction with new policy and planning initiatives that increase awareness and participation among the relevant groups. At the municipal level, for example, newly established food-policy councils have the capacity to help stimulate each model described above. Legislation such as the Community Food Security Act and the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act can stimulate transportation initiatives that promote food access through community grants.

Conclusion

The burden faced by people who rely on transit isn’t simply inconvenience. Transit-dependence frequently means lack of access to the most basic opportunities and resources, including food. Without adequate food outlets in their neighborhoods – not even a simple supermarket- these people are denied a minimal, healthful standard of living. They end up shopping at small corner stores, paying higher prices for less selection and lower quality items, which results in poor nutrition. Or, if they do venture outside their neighborhood, they’re forced to take long trips on transit along routes that do not coincide with their usual travel patterns.

Transportation planners have an opportunity to help alleviate their problem by improving transit services in low-income urban areas. By adapting small-vehicle paratransit modes to link supermarkets with homes, improved public transit may improve the quality of life for people who don’t own cars.

Further Readings

L. Ashman, J. De la Vega, M. Dohan, A. Fisher, R. Hippler, and B. Romain, Seeds of Change: Strategies for Food Security for the Inner City (Los Angeles: UCLA, Department of Urban Planning, June 1993).

Robert Cervera, “Commercial Paratransit in the United States: Service Options, Markets and Performance,” 1996. UCTC No. 299.

City of Cambridge, Community Development Department, Supermarket Access in Cambridge, Report to the Cambridge City Council (Cambridge: COD, December 19, 1994).

City of Los Angeles, Community Development Department, Hunger and Food Insecurity In Los Angeles: Findings of the Voluntary Advisory Council on Hunger: Final Report (Los Angeles: VACH, April 1996).

L. Cotterill and A. Franklin, The Urban Grocery Store Gap, Food Marketing Policy Center (Storrs: University of Connecticut, April 1995).

Public Voice, No Place to Shop: Challenges and Opportunities Facing the Development of Supermarkets in Urban America (Washington DC: Public Voice for Food and Health Policy, 1996).

Youngbin Yim, “Shopping Trips and Spatial Distribution of Food Stores,” 1993. UCTC No. 125.