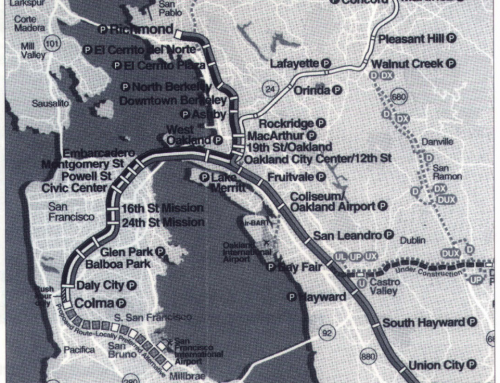

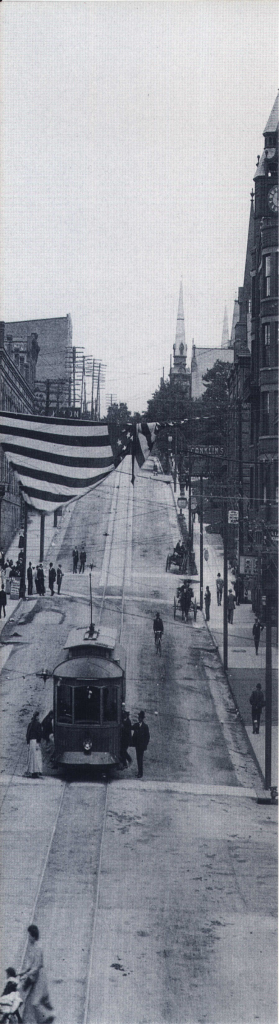

Several years ago, I commuted to work on BART, traveling from Oakland’s Rockridge station to downtown San Francisco. Although I could have used another station closer to my Berkeley home, I preferred Rockridge, with its bustling commerce, well-lit sidewalks, and village-like atmosphere. It seemed that the neighborhood’s residents had easy access to everything: a variety of restaurants, a library, supermarkets and specialty gourmet shops, health clubs, bookstores, professional offices, and, perhaps most significantly, buses and BART.

Several years ago, I commuted to work on BART, traveling from Oakland’s Rockridge station to downtown San Francisco. Although I could have used another station closer to my Berkeley home, I preferred Rockridge, with its bustling commerce, well-lit sidewalks, and village-like atmosphere. It seemed that the neighborhood’s residents had easy access to everything: a variety of restaurants, a library, supermarkets and specialty gourmet shops, health clubs, bookstores, professional offices, and, perhaps most significantly, buses and BART.

I know Rockridge isn’t perfect, but it seems to exemplify how a community can benefit from proximity to transportation facilities. Indeed, many planners believe that the ramifications of building a transit line in one area may extend far beyond providing transportation service. They say a transit stop may stimulate construction of housing and retail and office buildings, ultimately boosting the local economy and invigorating civic activity. For people without cars, the availability of transit can transform their lives, if it supplies their means of accessing schools, jobs, and basic necessities.

Transportation systems seem to do more than just move people from one place to another. Some say an ideal transportation system can generate new land use patterns, revitalize urban centers, and create vibrant, pedestrian-oriented neighborhoods like Rockridge. Transforming our inner cities in those ways would raise the living standards of low-income urban dwellers.

But if transportation infrastructure can accomplish these feats, why have so many well-intended efforts failed?

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Tridib Banerjee contemplate this question after examining the Blue Line route between Long Beach and downtown Los Angeles. Planners had expected the lightrail line to trigger upscale urban development around stations. But the researchers instead found empty fields, dilapidated buildings, and classical inner-city urban decay. So, they ask, what went wrong? Their review seeks to identify the missing elements that prevent transit-based development.

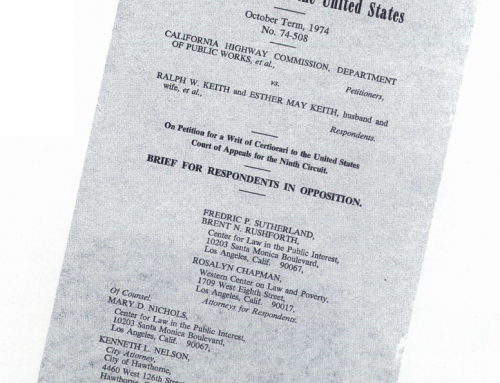

In a parallel review of IA’s Century Freeway, Joseph DiMento, Drusilla van Hengel, and Sherry Ryan looked at the effects of a public- interest lawsuit on the road’s three-decade-long development process. The litigation required state and local officials to submit detailed environmental impact reports and required highway builders to construct housing for those displaced by the freeway. Today, construction of transportation infrastructure requires consideration of affected residents’ civil rights, which should minimize potential harm to poor, often powerless, communities.

Undeterred by past failures, Michael Bernick explores the prospects for rail-induced subcenters at BART station sites – “transit villages,” he calls them – especially at an inner-city Oakland station. He acknowledges that BART has so far failed to fulfill its promise to induce such transit villages. The lesson to be learned, he suggests, is that active institutional engagement must accompany increased access for the land market to respond.

Recognizing the link between transportation and access to food, Robert Gottlieb and Andrew Fisher propose using transit services as a means to help low-income residents obtain adequate nutrition. They say that both grocers and transportation agencies can improve living standards for those without cars, by bringing shoppers to stores and delivering groceries to homes. Once again, they demonstrate that good transportation is both essential to urban life and a critical contributor to human welfare.

Restating a question that Peter Hall and Adib Kanafani asked in a debate in the Spring 1994 edition of ACCESS, David Levinson asks whether high-speed trains can compete with airlines in California’s intermetropolitan corridor. He and his Berkeley colleagues conducted a detailed analysis of the various costs associated with the competing modes and conclude that the train can’t beat the plane, either in speed or economics. However systematic and rigorous their analysis, their findings alone won’t resolve the continuing debates surrounding high-speed rail. But they must surely be accounted in those deliberations.

While most transportation improvements generate heated debate, the Freeway Service Patrol in California – a fleet of 270 tow trucks that patrol roadways and clear traffic incidents – has so far enjoyed unanimous praise. Robert L. Bertini reports on this state and municipal-sponsored program that effectively aids motorists – free of charge. The tow trucks are so effective in reducing incident caused delay that they’ve been dubbed the Guardian Angels of the Freeways.

Overall, people without cars are substantially less mobile: 46 percent of all adults in carless households took no trips on a sample day, compared with 21 percent in the general population.

Between 1960 and 1990, the number of US households without cars declined to only 9.2 percent. Richard Crepeau and Charles Lave seek to identify the typical carless household and to learn how well its members get around. They find that the mobility of people without cars relates to their location, employment, income, sex, education, and especially age. Overall, people without cars are substantially less mobile: 46 percent of all adults in carless households took no trips on a sample day, compared with 21 percent in the general population.

Their findings suggest to me that, if transit villages or Rockridge centers really can happen, perhaps they’d offer people without cars the easiest access to desired destinations. Perhaps they’d provide satisfying homesites for those who are housebound – as well as for people like me.

-Luci Yamamoto

Editor