In 1990 Los Angeles inaugurated the Blue Line amidst much fanfare as the first increment of a long-awaited light-rail system. The rail line connects downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach, traversing twenty-two miles of the poorest and most neglected neighborhoods in South Central Los Angeles. After six years, ridership has risen significantly, but areas around stations remain unchanged – disinvested, forsaken, and decaying – denying planners’ dreams of transit villages and depriving surrounding communities of their hopes for a better economic future.

Gertrude Stein’s cutting line about the lack of “there” in Oakland is even more appropriate to the Blue Line corridor. Four essential ingredients are missing: the sheer presence of people and activities near stations, a robust local economy, sustained institutional and political commitment, and neighborhood amenities that might entice investors to locate here. The absence of these attributes reflects the widening chasm between romantic visions of New Urbanism and the messy realities of inner-city life and politics.

Transit Corridor Planning

A fundamental tradeoff in metropolitan rail transit planning pits cost versus ridership. To locate a rail line through existing concentrations of activities and populations may make for numerous riders, but it also makes for higher costs of easements and capital improvements. It may also mean slower speeds, if trains must run on city streets regulated by traffic signals. So transit planners tend to select existing railroad lines, preferably abandoned ones, usually at the margins of built-up areas and away from activity centers. They can thus reduce cost and duration of construction and afford longer routes, while keeping travel times competitive with other alternative modes. But old rail alignments no longer match current riders’ origins and destinations or come near contemporary concentrations of people and activities, especially in Los Angeles.  Unlike cities of the East, LA’s land use patterns are the legacy of automobile- based, not railroad-based, transportation systems. Hence they are marked by spatial dispersion and comparatively fewer subcenters.

Unlike cities of the East, LA’s land use patterns are the legacy of automobile- based, not railroad-based, transportation systems. Hence they are marked by spatial dispersion and comparatively fewer subcenters.

In the short run, old railroad rights-of-way may be financially feasible and politically expedient. But at present, developments there are unlikely to improve the mobility or accessibility of those who most need services. In the absence of sustained public investment, they are also unlikely to turn transit systems into catalysts for economic development and neighborhood improvement.

Blue Line’s location is a case in point. The alignment was chosen by the political leaders of the county and city of Los Angeles. They saw linking the downtowns of Los Angeles and Long Beach as an important first step toward a region-wide rail-transit network throughout the Los Angeles metropolis. Once voters approved Proposition A in 1980, rail-transit advocates sought to get a rail project built as cheaply and quickly as possible. They hoped thus to become a legitimate candidate for future federal and state funds, and to show that Los Angeles can deliver rail transit.

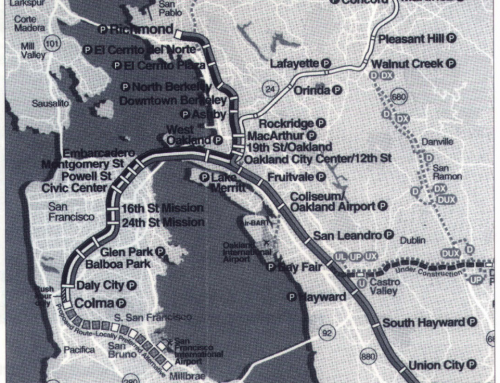

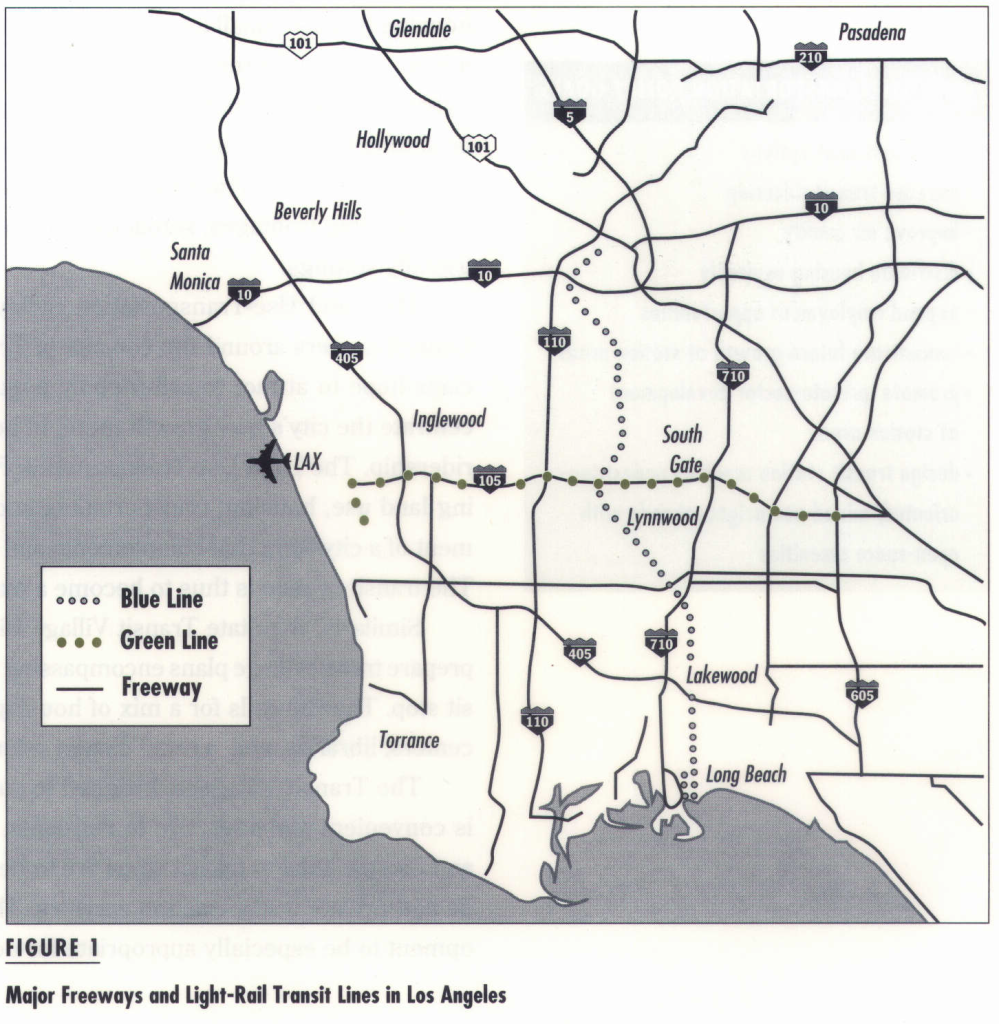

The existing Pacific Electric track that ran through the industrial corridor between Los Angeles and Long Beach provided a golden opportunity from the standpoint of economy and expediency. Paradoxically, however, the alignment was incompatible with the Centers Concept Plan, the only extant policy directive for Los Angeles’s future growth. LA’s answer to critics of its dispersed urban form was to try to induce a hierarchy of urban subcenters connected and induced by transit links (See Figure 1).

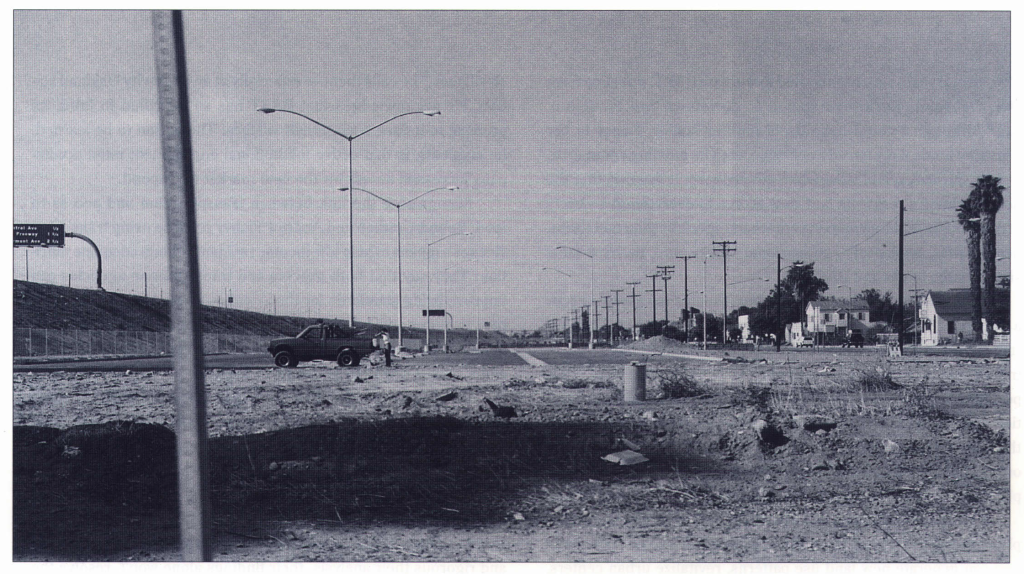

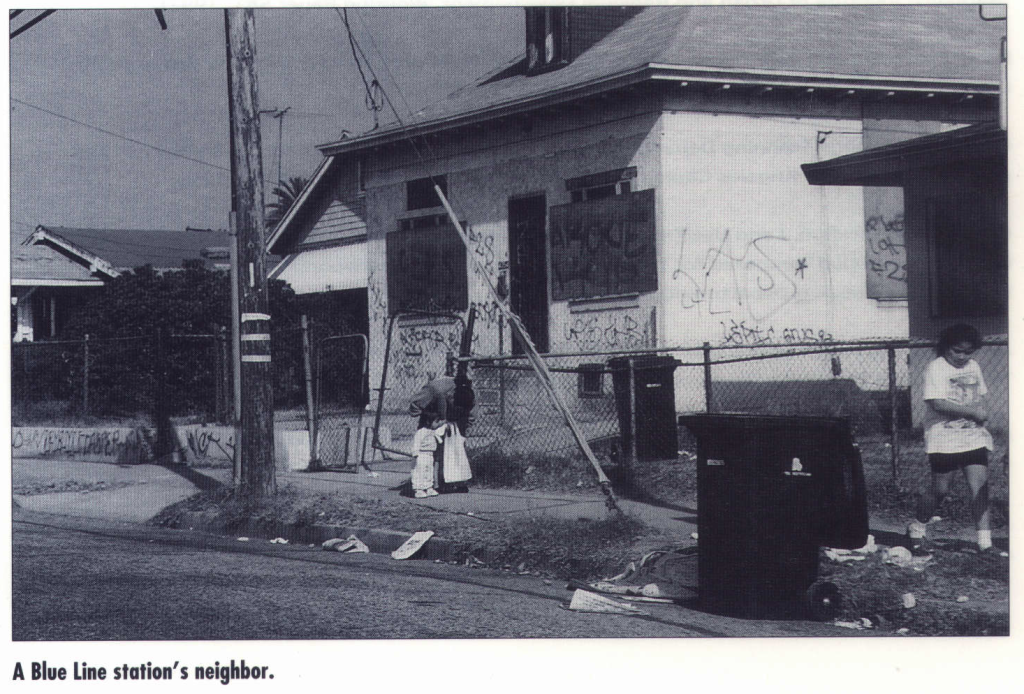

It seemed not to matter that Pacific Electric’s alignment had seen its day long ago and that it now passed through vast segments of “urban wilderness,” abandoned areas that contain only industrial warehouses, toxic waste dumps, industrial backlots, storage yards, and the like. Although improving access, mobility, and the economic potential of inner-city poor people drove much of the rhetoric underlying Blue Line planning, the rail has so far delivered very little to these groups. During the past six years there has been almost no visible improvement or development in the neighborhoods around most stations. The prospect of station neighborhoods with a mix of residential and commercial services remains a dream.

Popular Notions of Transit Village and New Urbanism

In recent years city planners and transit officials have promoted the idea of using rail-transit stations as instruments of development. Since 1990, much-touted design guidelines have sought to shape transit-oriented development in the city of San Diego and in Sacramento County. Other  cities have followed suit. In 1993 the city of Los Angeles and the Metropolitan Transit Authority formulated guiding principles for station-area development. In 1994 the California Legislature enacted a Transit Village Bill promoting such planning efforts.

cities have followed suit. In 1993 the city of Los Angeles and the Metropolitan Transit Authority formulated guiding principles for station-area development. In 1994 the California Legislature enacted a Transit Village Bill promoting such planning efforts.

A transit-oriented-development (TOD), as defined by Peter Calthorpe, a leading proponent of New Urbanism, is a mixed-use community, typically within a quarter-mile radius of a rail station and its adjacent commercial neighbors. The design, configuration, and mix of buildings and activities emphasize pedestrian-oriented environments and encourage use of public transportation, while accepting the presence of automobiles. While the elementary school was the focus of Clarence Perry’s classic neighborhood unit plan of the 1930s, the rail-transit stop is expected to become the new symbolic and geographic center.

New Urbanism advertises an alternative to automobile-generated urban sprawl by promoting compact city settings and lifestyles that are not dependent solely on cars. TOD policies envision villages surrounding transit stops with mixed-use commercial areas containing retail shops and offices. Larger core areas might combine major supermarkets, restaurants, entertainment outlets, and light-industry factories. A variety of housing types – small-lot single-family homes, townhouses, condominiums, and apartments – should promote denser neighborhoods than in typical suburban settings. Urban open spaces should furnish focal points for community activity. Streets should be settings for social interaction and active community life, not just means for efficient circulation of cars. Transit centers should have wide sidewalks, street trees, and seating. Building frontages, setbacks, and entries should shelter and augment pedestrian-friendly settings.

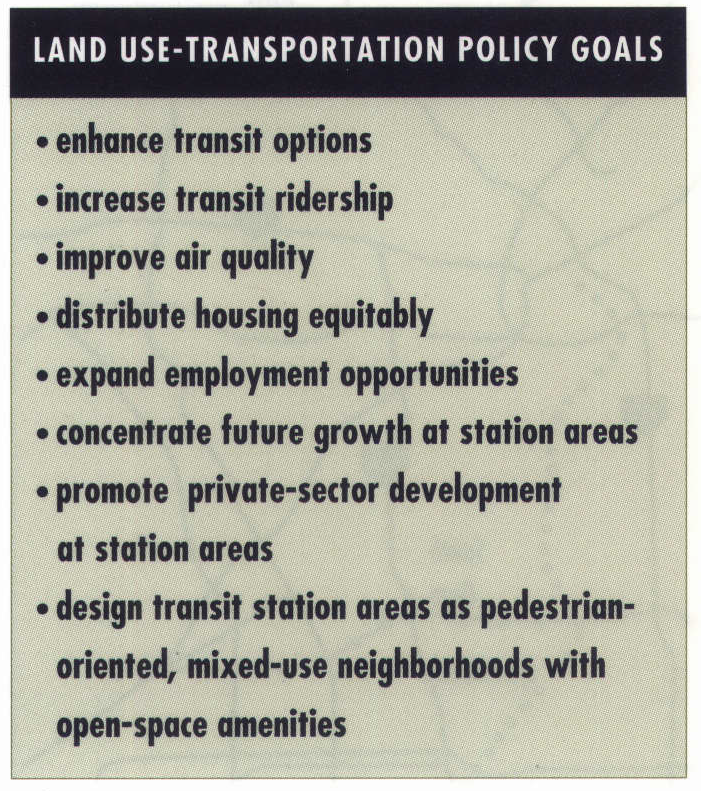

The Land Use-Transportation Policy formally adopted by the Los Angeles City Council centers around the concept of Transit-Oriented Districts. Planners and politicians hope to attract transit-friendly populations to areas around stations and to concentrate the city’s new growth there, in hopes of improving these areas and increasing ridership. The Land Use-Transportation Policy states a long-term strategy for integrating land use, housing, transportation, and environmental policies toward the development of a city form that complements and maximizes use of the region’s transit system. The transit system is thus to become a major instrument for civic betterment.

While the elementary school was the focus of Clarence Perry’s Classic neighborhood unit plan of the 1930s, a rail-transit stop is expected to become the new symbolic and geographical center.

Similarly, the State Transit Village Bill authorizes California cities and counties to prepare transit village plans encompassing areas within a quarter-mile radius of each transit stop. The Bill calls for a mix of housing types and other land uses, such as day-care centers, libraries, and a retail district oriented to each transit station.

The Transit Village is designed to support a socially amicable neighborhood that is convenient and attractive to residents, workers, shoppers, and visitors. Pedestrian and bicycle links to transit stops are to be supplemented by connections to other public and private transportation services. The Bill’s authors expect transit-village development to be especially appropriate for depressed inner-city neighborhoods.

Blue Line Station Neighborhoods

Despite all these well-intended proposals for station-area development, residents in the Blue Line’s environs have yet to enjoy economic growth or physical improvement. It is certainly plausible to attribute market nonresponse to economic recession, downturn in the real estate market, the 1992 riots, or other external causes. However, our analysis leads us to conclude that the problem is more fundamental than that.

First, the station areas are basically devoid of any significant concentration of population or activities. Density at some stations increases as one moves away from transit stops.

Second, most station areas lack any of the minimal physical amenities intrinsic to neighborhood livability. Parks, playgrounds, convenience stores, specialty businesses, and restaurants are conspicuously absent. Inner-city residents instead must endure the presence of unwanted elements such as billboards, liquor stores, electric transmission lines, and other obtrusive features in their residential areas.

Third, station areas show signs of abandonment and disinvestment. Public infrastructure is poorly maintained or serviced. Images of barbed- wire, chain-link fences, trash, and graffiti dominate the urban landscape, reflecting what some call the “broken window syndrome.”

wire, chain-link fences, trash, and graffiti dominate the urban landscape, reflecting what some call the “broken window syndrome.”

Fourth, the above conditions are exacerbated (if not partly caused) by high crime rates and negative perceptions of these areas. A broken window left unrepaired sends a signal that social services are inadequate, making it more likely for potential criminals to prey on residents and properties.

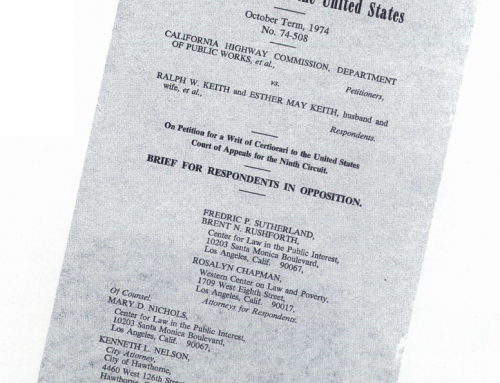

Fifth, in addition to – and despite – poor market appeal, the property value around stations and in South Central Los Angeles remains relatively high. This paradox, which contributes to the absence of investors, is the likely consequence of transportation improvements recently completed or forthcoming in this area: the 105 Freeway, the Green Line, doubledecking of the the 110 Freeway, and the proposed Alameda Corridor development. Paralleling our own research, two other studies commissioned by the MTA and the Los Angeles Planning Department are pessimistic about development near transit stations, at least in the short run.

The first study reports three types of feasibility gaps: (1) projects located near Blue Line stations fail to “pencil out” because projected revenues will not sustain an acceptable rate of return; (2) it is extremely difficult and costly to assemble lots for a project site because the corridor includes a multitude of small lots and absentee land owners; and (3) prospective house buyers often cannot meet credit requirements stipulated by most housing programs.

The second study finds that even assuming improved market conditions the rates of return on private investment fail to compete with other investment opportunities. Projected returns improve, however, with below-market interest and land writedown, in combination with fee mitigation and expedited approvals.

Weak Public Initiative

It is reasonable to conclude, then, that investors are unlikely to invest in redeveloping these decaying districts unless enticed by incentives. As with the early urban renewal programs, government must assume a proactive role if transit- oriented developments are to emerge. Among potentially effective public actions, we suggest land assembly by transit or redevelopment agencies, financial subsidies and incentives such as lowinterest loans, tax-exempt financing, land writedowns, financing of improvements, and rent subsidies.

Are rail transit agencies willing to invest in risky inner-city projects? So far, the answer for the Blue Line is clearly no. Strong public initiatives and commitments for restructuring development patterns at stations have been absent. Initiatives by localities have been lukewarm at best. The responsible transit agency has not been able to pursue an aggressive policy of land purchasing or development around the stations. As a result, it now holds only thirty acres in station areas. Prospects of village-type developments remain dubious, given MTA’s limited land holdings and its reluctance or inability to undertake large-scale ventures given its current fiscal constraints. The agency’s priorities have been guided by the political exigency of developing other lines in the metropolitan region rather than trying to make this one work better.

The Fallacy of Visions

The presumption of transit-induced development- deeply rooted in many planners’ visions of ideal community form and in the legacy of streetcar suburbs – does not seem to apply to inner-city neighborhoods. The New Urbanists’ romantic image of a transformed inner city stands in stark contrast with the decay, unemployment, poverty, and crime that characterize these neighborhoods.

A transit system cannot by its mere presence catalyze miracles in the inner city. In that sense the notion of the modern transit village will remain a bourgeois utopia unless strong political and institutional commitments are made.

It takes more than urban-design guidelines and rail lines to create an inner-city transit neighborhood. It takes sustained institutional commitment, political will, a viable local economy, community participation, and substantial financial support to override the major obstacles that confront development there. Unfortunately for the Blue Line’s low-income neighborhoods, those necessary qualities are not yet there.

Further Readings

Tridib Banerjee and William Baer, Beyond the Neighborhood Unit: Residential Environments and Public Policy (New York: Plenum, 1984).

Michael Bernick and Jason Munkres, “Designing Transit Based Communities,” (Berkeley: Institute of Urban and Regional Development, Working Paper 581, 1992).

Peter Calthorpe and Associates, Design Guidelines/Final Public Review Draft for Sacramento County Planning Community Development Department, 1990.

City of Los Angeles Planning Department, Land Use/Transportation Policy for the City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, 1993.

Cordoba Corporation, Land Use/Transportation Policy Feasibility Analysis and Recommendations for Implementation (prepared for Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority and City of Los Angeles Planning Department), 1993.

Anastasia Loukaitou-5ideris and Tridib Banerjee, “Form Follows Transit? The Blue Line Corridor’s Development Potentials,” 1994. UCTC No. 259.

Meza and Madrid Development, Inc., Blue Line Affordable Housing Study (prepared for Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority), 1991.

James Q. Wilson and J.Q. Kelling, “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety,” Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 29, 1993.