Besides having to use our air conditioner only occasionally now, one of the nicest things about moving to Davis, California, last year after nine years in Austin, Texas, has been the biking. Before the end of our second week here, we had bought a bike trailer so we could commute by bike to campus with our two pre-schoolers in tow. The purchase was a sort of initiation rite: the city of Davis estimates there are more bikes in Davis than people, and I suspect that family-oriented Davis accounts for a significant share of all bike trailers sold in the US. I confess that over the past year we didn’t always bike to campus. But in that time we put less than five thousand miles on our primary car, and got some exercise along the way.

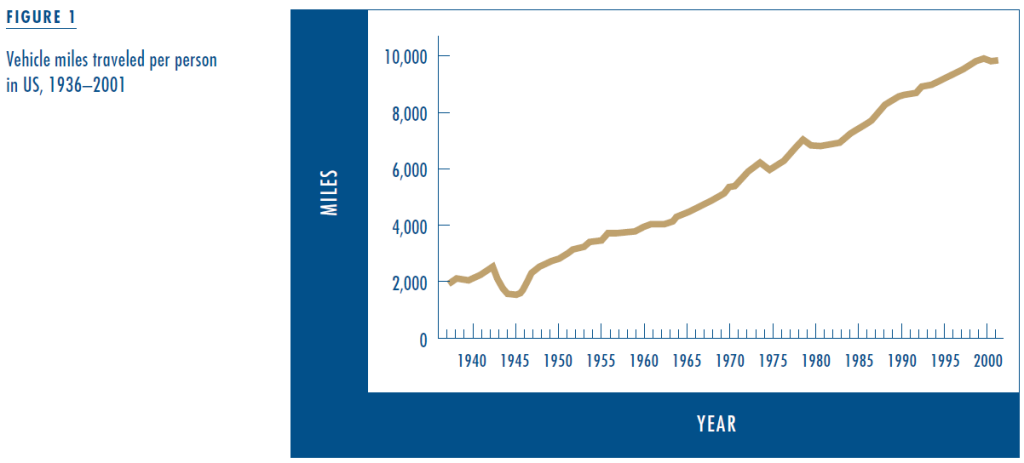

We are definitely bucking the trend by choosing to drive less. In 2001, according to the Nationwide Household Transportation Survey, the typical 35- to 44-year-old American spent over eighty minutes a day in a car, the average American household drove over 31,000 miles, and the average American car was driven nearly 13,000 miles. The growth in total vehicle miles traveled in the US has continued unabated for decades, growing two-and-a-half times as fast as the nation’s population between 1936 and 2001, according to the US Department of Transportation’s Highway Statistics (Figure 1). A slight leveling off in the last couple of years may prove to be no more than a blip in the relentless trend toward more driving.

We are definitely bucking the trend by choosing to drive less. In 2001, according to the Nationwide Household Transportation Survey, the typical 35- to 44-year-old American spent over eighty minutes a day in a car, the average American household drove over 31,000 miles, and the average American car was driven nearly 13,000 miles. The growth in total vehicle miles traveled in the US has continued unabated for decades, growing two-and-a-half times as fast as the nation’s population between 1936 and 2001, according to the US Department of Transportation’s Highway Statistics (Figure 1). A slight leveling off in the last couple of years may prove to be no more than a blip in the relentless trend toward more driving.

Driven To Drive

Although Americans seem to complain more and more about how much time they spend in the car (or at least how much time they spend stuck in traffic), we also have growing evidence that they often choose to drive more than they really need to. Studies by my colleagues Pat Mokhtarian and Ilan Salomon have shown that travel has its own intrinsic value—“a desire to travel for its own sake”—and that this is likely to lead to more travel than necessary for mandatory and maintenance activities. My own study in Austin found that as much as fifty percent of driving associated with trips to the supermarket can be attributed to the choice to shop at stores other than the one closest to home— further suggestion of more driving than necessary. These studies raise an interesting question: to what degree are we driving more because we have to, and to what degree are we driving more because we choose to?

In an ongoing study of this question sponsored by the Southwest Region University Transportation Center, my colleagues and I found the answer is some of both. In a series of focus groups and in-depth interviews, we explored the ways and reasons for which people drive more than they, in theory, need to—what we called “excess driving.” We found convincing evidence that people often take extra trips, choose longer routes, pick more distant destinations, and opt for the car over other possible travel modes. They make these choices for various reasons, including among others enjoyment of driving, enjoyment of activities while driving, desire for variety, habit, laziness, and poor planning. Said one participant, “There’s just something about getting in the car and getting out on a country road.” When pressed, people acknowledge that they’re driving more than they really need to. But the driving they want to eliminate is, not surprisingly, the driving they need to do rather than the driving they choose to do.

In an ongoing study of this question sponsored by the Southwest Region University Transportation Center, my colleagues and I found the answer is some of both. In a series of focus groups and in-depth interviews, we explored the ways and reasons for which people drive more than they, in theory, need to—what we called “excess driving.” We found convincing evidence that people often take extra trips, choose longer routes, pick more distant destinations, and opt for the car over other possible travel modes. They make these choices for various reasons, including among others enjoyment of driving, enjoyment of activities while driving, desire for variety, habit, laziness, and poor planning. Said one participant, “There’s just something about getting in the car and getting out on a country road.” When pressed, people acknowledge that they’re driving more than they really need to. But the driving they want to eliminate is, not surprisingly, the driving they need to do rather than the driving they choose to do.

Reducing The Need

So what does this mean for planners? The easier problem to tackle is the driving we do by necessity rather than choice. Although “need” is subjective, it’s clear that most Americans do need to drive as they go about their daily lives, at least given the choices they’ve made about where to live, where to work, and what to do with their free time. Planners can create policies that will help lessen this need by bringing destinations closer to origins and by improving the viability of alternative modes. The Congress for the New Urbanism, for one, has been a vocal promoter of this approach; its charter states that “neighborhoods should be compact, pedestrian-friendly, and mixed use” and that “many activities of daily living should occur within walking distance.”

Davis is a good example of how this approach can work, although it looks a lot more like typical suburban America than what the new urbanists have in mind. In Davis, I can live in my 2,300-square-foot house on a 10,000-square-foot lot on a cul-de-sac in a 1970s subdivision, but be within two miles of work and a half-mile of a supermarket, Peet’s coffee, and two burrito shops. I’m also linked to work by a relatively direct bus route and to the entire community by an extensive system of greenbelt trails and on-street bike lanes.

That Davis residents have less need to drive is a matter of plan rather than chance.

In 1966, the Davis City Council made a conscious effort to promote bicycle use, and today the city has nearly fifty miles of bike lanes and fifty miles of bike paths in an area of only ten square miles or so. In 1973, in response to forecasts of explosive growth, the city adopted a general plan designed to avert suburban sprawl and its environmental impacts. Guided by this plan, the city adopted policies to encourage infill development and the distribution of multi-family housing throughout the city, meaning that densities everywhere are relatively high, at least by California suburban standards. The city has also followed through on its policy of locating services conveniently within each neighborhood with the explicit goal of moderating the length of trips and facilitating walking, biking, and transit as alternatives to driving.

In 1966, the Davis City Council made a conscious effort to promote bicycle use, and today the city has nearly fifty miles of bike lanes and fifty miles of bike paths in an area of only ten square miles or so. In 1973, in response to forecasts of explosive growth, the city adopted a general plan designed to avert suburban sprawl and its environmental impacts. Guided by this plan, the city adopted policies to encourage infill development and the distribution of multi-family housing throughout the city, meaning that densities everywhere are relatively high, at least by California suburban standards. The city has also followed through on its policy of locating services conveniently within each neighborhood with the explicit goal of moderating the length of trips and facilitating walking, biking, and transit as alternatives to driving.

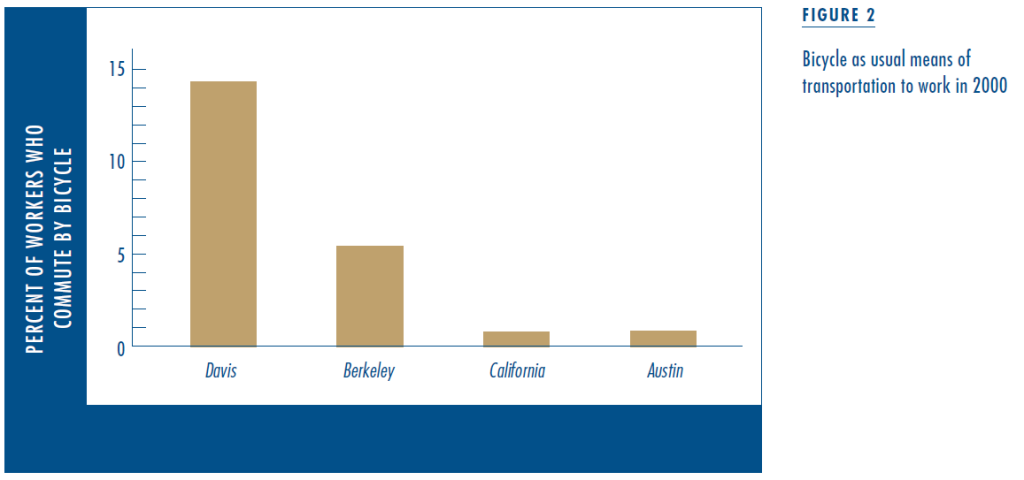

Of course, having the choice to drive less doesn’t mean that people will actually choose to drive less. Although most of my colleagues in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy here at UC Davis do bike to work, not all of my Institute of Transportation Studies colleagues do. I’ve been surprised at how few of my neighbors use bikes. Most of them work outside of Davis but I don’t often see them biking to the farmer’s market or to the library or to the pool the way we do. According to the 2000 US Census, over fourteen percent of Davis residents usually bike to work. This is less than you might expect given the town’s reputation, but it’s more than Berkeley and considerably more than California as a whole—or than Austin (Figure 2). Still, everyone I talk to in Davis appreciates the option not to drive, even if they rarely take advantage of it. (I also believe that even the people who do not drive less are taking advantage of the greenbelt system to walk and bike more for exercise—but that’s another topic for discussion.)

Of course, having the choice to drive less doesn’t mean that people will actually choose to drive less. Although most of my colleagues in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy here at UC Davis do bike to work, not all of my Institute of Transportation Studies colleagues do. I’ve been surprised at how few of my neighbors use bikes. Most of them work outside of Davis but I don’t often see them biking to the farmer’s market or to the library or to the pool the way we do. According to the 2000 US Census, over fourteen percent of Davis residents usually bike to work. This is less than you might expect given the town’s reputation, but it’s more than Berkeley and considerably more than California as a whole—or than Austin (Figure 2). Still, everyone I talk to in Davis appreciates the option not to drive, even if they rarely take advantage of it. (I also believe that even the people who do not drive less are taking advantage of the greenbelt system to walk and bike more for exercise—but that’s another topic for discussion.)

The Challenge For Planners

What, if anything, do we do about driving by choice rather than necessity? I can tell you what they do in Texas: they try to accommodate it. Even coming from California, purported land of freeways, I was struck by the sense of entitlement Texans feel about driving. Texans seem to believe that driving anywhere they want at any time of day at seventy miles per hour or more is a fundamental right, at least on par with freedom of speech or maybe even property rights. In California, we seem to recognize that we’ll never be able to accommodate all the increased demand for driving coming from population growth, let alone continued increases in the rate of driving per person—and that for a variety of reasons we probably shouldn’t try. In its mission statement, Texas DOT prioritizes the “safe, effective and efficient movement of people and goods”; Caltrans, in contrast, pledges “a renewed emphasis on nonhighway transportation” on its website.

What, if anything, do we do about driving by choice rather than necessity? I can tell you what they do in Texas: they try to accommodate it. Even coming from California, purported land of freeways, I was struck by the sense of entitlement Texans feel about driving. Texans seem to believe that driving anywhere they want at any time of day at seventy miles per hour or more is a fundamental right, at least on par with freedom of speech or maybe even property rights. In California, we seem to recognize that we’ll never be able to accommodate all the increased demand for driving coming from population growth, let alone continued increases in the rate of driving per person—and that for a variety of reasons we probably shouldn’t try. In its mission statement, Texas DOT prioritizes the “safe, effective and efficient movement of people and goods”; Caltrans, in contrast, pledges “a renewed emphasis on nonhighway transportation” on its website.

A possible alternative to accommodating driving by choice is to discourage it through various forms of pricing, as many researchers have suggested in these pages. The implementation of congestion pricing, for example, could shift optional driving away from commute times, thereby freeing up capacity for necessary driving during peak hours. Strategies that make drivers pay for their travel more directly (e.g., pay-at-the- pump insurance) or that “internalize” externalities such as environmental impacts (e.g. emissions taxes) could lead to significant cutbacks in driving by choice. A problem with pricing is that it’s hard to apply it only to driving by choice and not also to driving by necessity, raising issues about equity that are challenging—though not insurmountable. So far, pricing strategies have garnered little political support; and in Texas, at least, pricing in the form of tolls is seen as a way to fund new road capacity to accommodate more driving rather than as a way to discourage it.

Based on a review of the research and lots of thinking about these issues, I say “no” to accommodating driving by choice, “possibly” to discouraging driving by choice, and an emphatic “yes” to doing what we can to reduce driving by necessity. We could have a protracted debate on the first two points, but this last point is one that I think all sides could eventually agree on. If we make it easier for people not to drive, everyone wins: those who can’t drive certainly win; those who can drive but would rather not also win; and even those who would never do anything but drive still win, not least because the time they save on necessary driving can be put to other uses, including more driving if they choose. Freedom of choice is fundamental to the American creed—that includes the freedom to choose to drive but also the freedom to choose not to drive. And that freedom is what I love about Davis.

Based on a review of the research and lots of thinking about these issues, I say “no” to accommodating driving by choice, “possibly” to discouraging driving by choice, and an emphatic “yes” to doing what we can to reduce driving by necessity. We could have a protracted debate on the first two points, but this last point is one that I think all sides could eventually agree on. If we make it easier for people not to drive, everyone wins: those who can’t drive certainly win; those who can drive but would rather not also win; and even those who would never do anything but drive still win, not least because the time they save on necessary driving can be put to other uses, including more driving if they choose. Freedom of choice is fundamental to the American creed—that includes the freedom to choose to drive but also the freedom to choose not to drive. And that freedom is what I love about Davis.

Further Readings

City of Davis Comprehensive Bicycle Plan.(May 2001: Davis, CA).

City of Davis General Plan Update. (May 2001:Davis, CA).

Congress for the New Urbanism. CNU: Congress for the New Urbanism. 2003.

Susan Handy. Accessibility- vs. Mobility- Enhancing Strategies for Addressing Automobile Dependence in the US. Prepared for the European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Roundtable 124: Transportation and Spatial Policies: The Role of Regulatory and Fiscal Incentives, Paris, 2002.

Susan Handy, Andrew DeGarmo, and Kelly Clifton. Understanding the Growth in Non- work VMT. Report No. SWUTC/02/167222 (February 2002: Southwest Region University Transportation Center, The University of Texas at Austin).

Susan Handy and Kelly Clifton, “Local Shopping as a Strategy for Reducing Automobile Dependence,” Transportation, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 317-346, 2001.

Susan Handy, Lisa Weston, and Patricia Mokhtarian. “Driving by Choice or Necessity? The Case of the Soccer Mom and Other Stories,” presented at the 82nd Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, January 2003.

Patricia Mokhtarian, Ilan Salomon, and Lothlorien S. Redmond. “Understanding the Demand for Travel: It’s Not Purely ‘Derived’,” Innovation, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 355-380, 2001.