Melvin M. Webber died two days after Thanksgiving in the Berkeley home where he and his wife Carolyn had lived peaceably for nearly half a century; they would soon have celebrated their golden wedding anniversary, but at the age of 86 his multiple myeloma cheated them of their festival. With him passed an era in the history of Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning, where he had spent nearly all his long academic life and to whose international pre-eminence he had so profoundly contributed.

His importance to planning as an academic discipline, not merely in the United States but even more so on the international scale, would never be measured in quantitative terms. Indeed, as with so many leading academic figures of his generation, by today’s standards his published output might appear negligible; in another time and place, he would have presented a problem for a harassed department head, struggling to raise collective output for a forthcoming Research Assessment Exercise. The truly astonishing fact was that his publications, though sparse, were of such extraordinary path-breaking quality. He transformed the way we thought about cities and about the ways we should go about planning them. Thomas Kuhn, when he published his celebrated book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in 1962, might have been writing about him. He was truly a paradigm breaker and a paradigm maker.

It was just at that time, in fact, that he made his first major contribution to the literature in the form of two essays which have been cited and cited again. Their wonderfully intriguing titles aptly suggested both their subversive content and their elegantly classical style. “Order in Diversity: Community without Propinquity” was published in 1963, in a symposium, Cities and Space: The Future Use of Urban Land, edited by Lowdon Wingo of Resources for the Future, a Washington, DC think tank. “The Urban Place and the Nonplace Urban Realm” appeared the following year in a volume Webber himself edited, Explorations into Urban Structure, which contained several other essays from his Berkeley department, reflecting its sparkling intellectual pre-eminence at the time.

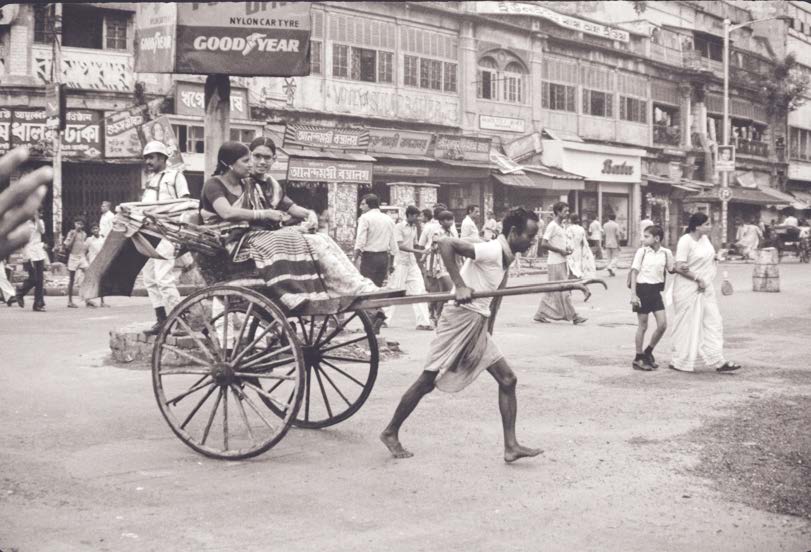

In them he argued, as he put it, that planners were seeking the wrong Holy Grail: they were obsessed with the concept of place, but place was rapidly becoming irrelevant in people’s lives, whether for their work or their residence or their patterns of consumption. The new service industries used immaterial inputs and had immaterial outputs, so were free to locate where they would; mass car ownership and freeway networks increasingly gave people the freedom to locate where they wished; and mass mobility gave the possibility of different lifestyles in all manner of places. Most significantly of all, he argued, people were losing their old ancestral attachment to places: they had complex and multi-layered social relationships, some local, some stretching across the world. What mattered was not the places where they happened to be, but the networks that connected them.

Looking back over more than forty years, it is evident even more so now than at the time how much this vision was a product of the uniqueness of Californian society in the early 1960s. It was, as I wrote years after,

…the high water mark of a certain self-created myth created by California about itself. The state was in the middle of its extraordinary boom years, fuelled by ten years of Cold War, by defense contracts and by the rise of Silicon Valley on the other side of the San Francisco Bay, except no one called it that then. Under the benign governorship of the late great Pat Brown, California was pumping its wealth into a huge investment program: into the brand new freeways that were everywhere multiplying, into massive expansion of the university system that would make it the greatest in the world.

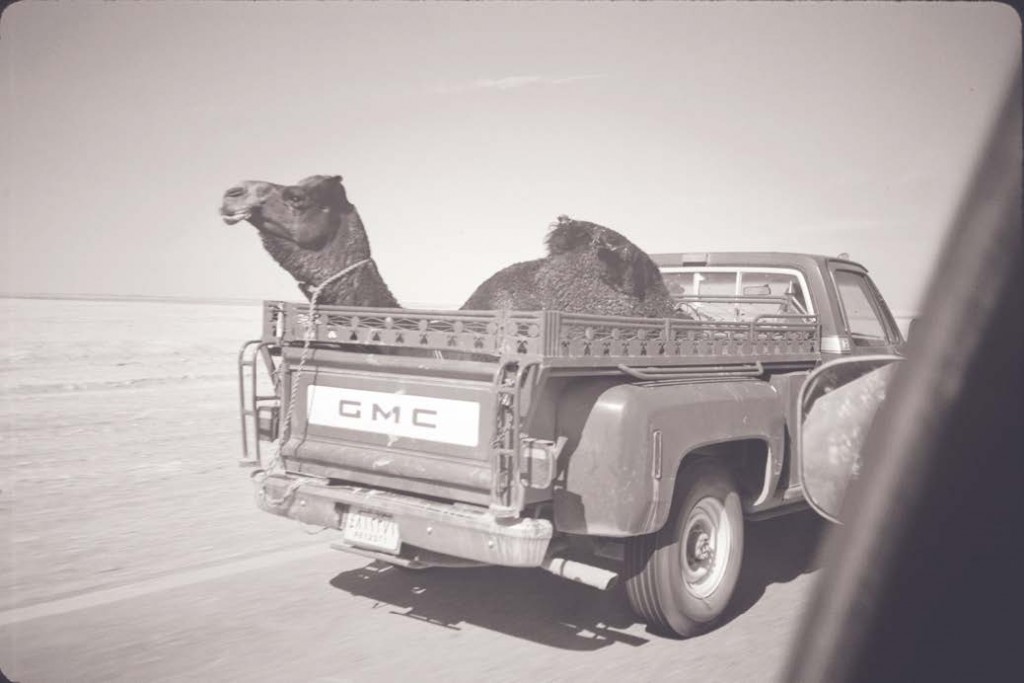

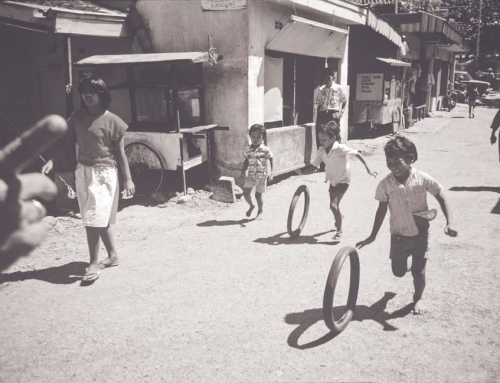

In consequence life in California was displaying characteristics that then appeared totally exotic but have now become commonplace across the affluent world, not least here in the UK. Already, people in what would soon be known as Silicon Valley changed employers and workplaces as casually as if buying a cup of coffee. Already, people would get into their cars and drive an hour to a giant shopping mall. Already, people took planes to anywhere as if they were buses. Already, people would go off at the drop of a hat for a weekend in Acapulco or Puerto Vallarta. Even more significantly, in that pre-Internet age, Californians would spend literally hours on the telephone, indifferent as to whether they were talking to someone a mile down the road or 3000 miles across a continent. In 1963, Mel Webber had seen the future of the world already arrived around him, and found that it worked.

It was an extraordinary time in human history, with the first vibrations across the Bay Area and the Berkeley campus of what soon after became that legendary Summer of Love in San Francisco. Ironically, no one could have been less personally attuned to that bizarre manifestation of mass human liberation than Mel himself. The very personification of New England rationality and slightly skeptical detachment, a sociologist/economist by training (and very much a scientist by inclination), he viewed the whole era with amused detachment, almost in the spirit of a social anthropologist. I will never forget the first class we co-taught at Berkeley in early 1974, a PhD seminar. Mel asked the students to make brief presentations of their research plans. After some reasonably coherent if slightly conventional proposals, it was the turn of an extremely intense female student at the corner of the table. She proposed, she announced, to study the contrast between the aggressive male-dominated alcohol-based culture and the all-embracing female marijuana-based culture. Mel took all this in his usual sympathetic way, gradually seeking to make a researchable topic out of it—with what result, I cannot now recall.

It was an extraordinary time in human history, with the first vibrations across the Bay Area and the Berkeley campus of what soon after became that legendary Summer of Love in San Francisco. Ironically, no one could have been less personally attuned to that bizarre manifestation of mass human liberation than Mel himself. The very personification of New England rationality and slightly skeptical detachment, a sociologist/economist by training (and very much a scientist by inclination), he viewed the whole era with amused detachment, almost in the spirit of a social anthropologist. I will never forget the first class we co-taught at Berkeley in early 1974, a PhD seminar. Mel asked the students to make brief presentations of their research plans. After some reasonably coherent if slightly conventional proposals, it was the turn of an extremely intense female student at the corner of the table. She proposed, she announced, to study the contrast between the aggressive male-dominated alcohol-based culture and the all-embracing female marijuana-based culture. Mel took all this in his usual sympathetic way, gradually seeking to make a researchable topic out of it—with what result, I cannot now recall.

Meanwhile, our intellectual exchanges—and his influence on other British academics like Peter Rayner Banham, who repaid the debt by writing what remains the best book ever written on Los Angeles—had led to an invitation to spend an academic year in London as Visiting Scholar at the newly-founded Centre for Environmental Studies, an urban think tank. That sojourn produced a two-part paper in the Town Planning Review that further developed his ideas in an international context, but even more importantly led to his appointment by Richard Llewelyn Davies as advisor on the master plan for Milton Keynes, then just starting gestation. No one present at those inaugural seminars will ever forget the power with which he argued for a town freed of all conventional concepts of place or hierarchy. The basic concept that emerged, stamping itself indelibly on the plan as finally drafted, was also powerfully influenced by the ideas of Christopher Alexander, an English émigré to Berkeley, and in particular by his essay “A City Is Not a Tree;” hierarchy and determinacy were out, freedom of action was the governing principle, and automobility would be the key. At a time when a bare half of all British households owned a car, it was an audacious vision, and MK (as it soon became known) became the town that many planners loved to hate. But to this day its citizens, significantly, hail the quality of life there. Mel passionately believed in planning for people and the way they wanted to live, not the way planners thought they ought to live: a very American, above all Californian, view of the world. It was some time after that, in 1976, that he published another of the infrequent pieces that could truly be described by that overworked word, seminal. “The BART Experience: What Have We Learned?” was a research monograph from the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, which he headed for many years. A group had been tasked with undertaking an independent review of the then-new Bay Area Transportation System, a remarkable initiative in its own right: designed as an express transit system for the entire region around the San Francisco Bay, sixty miles from San Rafael to San Jose, thirty miles from the Pacific Ocean to Concord and Walnut Creek. Like everything else in California at the time, it was a visionary and hugely ambitious attempt to provide a viable alternative to what was already the reality of mass automobility. Studying the result, Mel, who had much earlier been an advocate of the project, concluded that it had not succeeded in its basic objective. It was based, he said, on the false premise of extraordinarily high speed—eighty miles an hour under the Bay, between downtown Oakland and downtown San Francisco—and it ignored the basic fact that the dispersed pattern of residential development meant that people lived too far from the BART stations. In consequence, on a wet December or February morning—and there are many such in the California winter months—the typical East Bay commuter would get into her car and drive on to Highway 24, with the BART line running at speed through the central median. Commuters would reject the dash through the rain to the train, preferring to stay snug and dry, with the radio soothing their way through the gridlocked approach to the Bay Bridge toll plaza. BART could have worked for Paris, Mel concluded; the problem was that the Bay Area, and any American metropolis of similar ilk, wasn’t Paris. That lesson has since been relearned bitterly in other American cities; among transit planners, hope springs eternal.

Mel Webber believed in planning for the world as it actually was, working within the limits of the possible.

But Mel was never seduced by unattainable visions; his scientific bent, which he reinforced by assiduous reading of Scientific American, precluded that. He believed in planning for the world as it actually was, working within the limits of the possible. About that time he joined in an extraordinary intellectual collaboration with Horst Rittel, a German academic who spent half his academic year on the Berkeley campus. The result was a paper, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” published in the journal Policy Sciences in 1973. In it Rittel and Webber stated, “The easy problems have been solved. Designing systems today is difficult because there is no consensus on what the problems are, let alone how to resolve them.” They argued that there is a set of “wicked problems” that defy any possibility of solution by conventional rational approaches: the apparent solution might reveal or create another problem, even more complex than the last. That insight has reverberated through the field of public policy ever since, generating academic contributions almost without number.

During the 1970s, like many others of the Berkeley professoriate, Mel suffered not only intellectually but also personally from the Marxist ascendancy in the social sciences, with which he never successfully grappled—new generations of students complained that his reading lists were outdated—and which led him to be branded almost as a counter-revolutionary. Ironically, in his own professional career he was the very personification of the aphorism of Antonio Gramsci: Pessimism of the Intellect, Optimism of the Will. And, by another rare academic irony, Manuel Castells, appointed to join the Berkeley faculty in 1979 as the world’s leading exponent of Marxist urbanism, later drew heavily on Mel’s insights to develop his hugely influential idea of the network society.

Mel’s deep grounding in social reality caused him to continue to hold out against changing intellectual currents, especially the environmental movement that gained sway over the Marxist ascendancy on campuses like Berkeley in the late 1980s and 1990s. Appointed to a prestigious committee of the American Association for Arts and Sciences on the future of the automobile, he held out steadfastly against virtually the entire membership, continuing to extol the virtues of the car as a liberator of the human spirit. That deep stubbornness, based on a clear understanding of ordinary people and their needs and preferences, did not always endear him to colleagues. But it spoke to a rare integrity of the intellect.

His intellectual flashes of genius were lights that lit a steady and satisfying life of service to the university he loved. He was a major figure on the academic Senate. He ran the Institute of Urban and Regional Development for nearly twenty years, and also directed the Transportation Center where, right to the end of his days, he continued to edit the journal he had founded, ACCESS. Here, in 1990, against all his instincts but in a typical spirit of scientific curiosity, he gave me a small grant to study the possible future of high-speed rail in California. The report, written with three graduate students, led indirectly to the establishment of the California High-Speed Rail Authority, with one of those students, Dan Leavitt, as Deputy Director. One day not too distant, boosted by Governor Schwarzenegger’s conversion to environmentalism, the proposal—one of the biggest civil engineering projects in Californian history—will go before the voters. If it wins their approval, that would be another rare academic irony. Mel would doubtless say, as he said to me in life, that it was yet another example of wish fulfillment. Time alone will then tell if the old master was again right at the end.

His intellectual flashes of genius were lights that lit a steady and satisfying life of service to the university he loved. He was a major figure on the academic Senate. He ran the Institute of Urban and Regional Development for nearly twenty years, and also directed the Transportation Center where, right to the end of his days, he continued to edit the journal he had founded, ACCESS. Here, in 1990, against all his instincts but in a typical spirit of scientific curiosity, he gave me a small grant to study the possible future of high-speed rail in California. The report, written with three graduate students, led indirectly to the establishment of the California High-Speed Rail Authority, with one of those students, Dan Leavitt, as Deputy Director. One day not too distant, boosted by Governor Schwarzenegger’s conversion to environmentalism, the proposal—one of the biggest civil engineering projects in Californian history—will go before the voters. If it wins their approval, that would be another rare academic irony. Mel would doubtless say, as he said to me in life, that it was yet another example of wish fulfillment. Time alone will then tell if the old master was again right at the end.

His end was quintessentially characteristic: his colleagues and friends received an email, dated the day of his death, saying simply: “Goodbye. Mel.” Simply, rationally, with-

out fuss, he must have typed it and left it on his computer before he lay down to wait for death. It was, like so much he did and so much of what he was, quietly magnificent.