Employer-paid parking is an invitation to drive to work alone. Thus, it increases traffic congestion, air pollution, and energy consumption. To deal with problems created by employer-paid parking, I propose a minor technical change in the Internal Revenue Code. The proposal is that employers who subsidize employee parking should be required to offer employees the option to take a taxable cash travel allowance equal to the fair market value of the parking subsidy. Case studies and a statistical model suggest that offering employees the option to cash out their parking subsidies could reduce solo driving to work by 20 percent, reduce automobile travel to work by 76 billion miles per year, save 4.5 billion gallons of gasoline per year, eliminate 40 million metric tons of CO2 emissions per year, and increase tax revenues by $1.2 billion per year. These objectives would be accomplished by offering commuters the option to take taxable cash in lieu of a free parking space.

Employer-Paid Parking Encourages Solo Driving

Employer-paid parking is a matching grant: employers offer to pay the cost of parking if employees are willing to pay all the other costs of driving to work. Evidence from a variety of sources, including the 1990 Nationwide Personal Transportation Survey, shows that at least ninety percent of American commuters who drive to work pay nothing to park.

How strongly does employer-paid parking encourage solo driving to work? For the 50,000 solo drivers who receive employer-paid parking in downtown Los Angeles, the average parking subsidy is equivalent to 11 cents per mile driven. Their average parking subsidy is 16 times greater than the federal gasoline tax they pay for their commute trip. Thus, even an improbably huge increase in the gasoline tax would discourage fewer solo commute trips than free parking now encourages. Finally the average subsidy for commuter parking in downtown Los Angeles is almost 50 percent greater than the total cost of gasoline for the average commute trip. An employer’s offer of free gasoline for all employees who drive to work would be recognized as an environmental outrage, yet employer-paid parking is a much stronger financial incentive to drive to work.

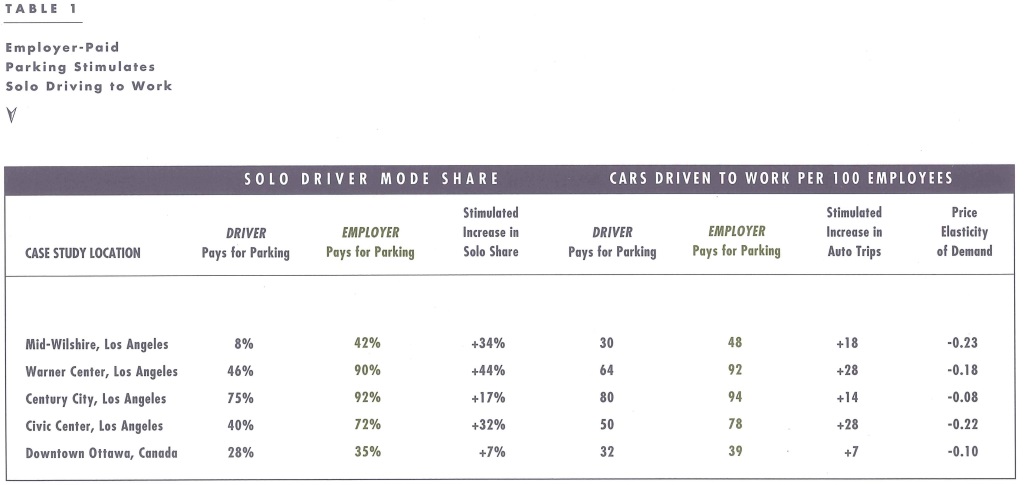

Table 1 summarizes the results of well-documented case studies of how employer paid parking stimulates solo driving to work. On average, employer-paid parking shifts 27 percent of all commuters into solo driving from other modes and stimulates 19 more cars to be driven to work for every 100 employees. Among solo drivers whose employers offer free parking, 41 percent drive solo only because their employers pay for the parking.

A survey of 5,000 commuters and their employers in downtown Los Angeles shows that employers spend $4.10 on parking subsidies for every $1 employees save on the total cost of parking and driving. This surprising disproportion between the large amount that employers pay for parking and the small amount that employees save on the total cost of parking and driving occurs because employer-paid parking so strongly stimulates spending on both parking and driving: the stimulus to parking demand inflates what employers must pay for parking, and the stimulus to solo driving diminishes what employees save on their total cost of parking and driving. On average, employer-paid parking stimulates a 33 percent increase in vehicle miles traveled to work per employee per year.

The Internal Revenue Code Encourages Employer-Paid Parking

The Internal Revenue Code classifies an employer’s payment for an employee’s parking as a tax-exempt fringe benefit for the employee. But if the employee pays for parking at work, the Code does not allow the employee to deduct the parking charge as a work related expense. Therefore, to take advantage of the tax-exemption for commuter parking, the employer must pay for the employee’s parking. The Code exempts employer-paid parking from more than just the Federal income tax. The exemption is automatically extended to Social Security taxes, state income taxes, unemployment insurance taxes, and all other payroll taxes. When these related exemptions are taken into account, $1 of employer-paid parking is worth more than $2 in taxable cash wage income for many employees. Therefore, the Code’s peculiar asymmetrical tax exemption for employer-paid (but not for employee-paid) parking is a clear and strong financial incentive that has inadvertently shifted the responsibility for paying for almost all commuter parking entirely from the employee to the employer, and has thus reduced the employee’s parking cost to zero.

The Internal Revenue Code classifies an employer’s payment for an employee’s parking as a tax-exempt fringe benefit for the employee. But if the employee pays for parking at work, the Code does not allow the employee to deduct the parking charge as a work related expense. Therefore, to take advantage of the tax-exemption for commuter parking, the employer must pay for the employee’s parking. The Code exempts employer-paid parking from more than just the Federal income tax. The exemption is automatically extended to Social Security taxes, state income taxes, unemployment insurance taxes, and all other payroll taxes. When these related exemptions are taken into account, $1 of employer-paid parking is worth more than $2 in taxable cash wage income for many employees. Therefore, the Code’s peculiar asymmetrical tax exemption for employer-paid (but not for employee-paid) parking is a clear and strong financial incentive that has inadvertently shifted the responsibility for paying for almost all commuter parking entirely from the employee to the employer, and has thus reduced the employee’s parking cost to zero.

No other fringe benefit is tax-exempt when paid for by the employer but taxable when paid for by the employee. Thus, the tax exemption for employer-paid parking subsidies is a unique, deliberate, and specially targeted tax subsidy that has the unfortunate, unintended, and largely unnoticed effect of stimulating a huge increase in the number of commuters who drive to work alone.

Cashing Out Employer-Paid Parking

Ridesharing and mass transit advocates have argued for years to end this tax bias because it aggravates traffic congestion and air pollution, and stimulates gasoline consumption. But eliminating a tax exemption that benefits so many workers – at all income levels – is politically difficult. Thus, it seems quixotic to try to eliminate the special tax exemption for employer-paid parking, no matter how much harm it does.

Given the general popularity of employer-paid parking subsidies, a long step in the right direction would be to amend the Internal Revenue Code’s definition of tax-exempt “qualified parking,” as follows:

QUALIFIED PARKING – The term “qualified parking” means parking provided to an employee on or near the business premises of the employer … if the employer offers the employee the option to receive, in lieu of the parking, the fair market value of the parking, either as a taxable cash commute allowance or as a mass transit or ridesharing subsidy.

The text in roman type is the existing definition of tax-exempt “qualified parking” in Paragraph (5) of Section 132 (f) of the Internal Revenue Code, and the italic text is the proposed amendment.

This amendment retains the popular tax exemption for employer-paid parking but would require that employers offer their employees the option of cash or a mass transit or ridesharing subsidy in lieu of the tax-exempt parking. The proposal has several important advantages:

- Free Parking Will Have an Opportunity Cost. When commuters are offered the choice between free parking or nothing, the parking has no opportunity cost and is therefore over-used.

But asking commuters to choose between a free parking space or its cash value makes it clear that parking has a cost, which is the cash not taken. The new “price” for taking the “free” parking would increase the perceived cost of solo driving to work.

But asking commuters to choose between a free parking space or its cash value makes it clear that parking has a cost, which is the cash not taken. The new “price” for taking the “free” parking would increase the perceived cost of solo driving to work. - Cashing Out Will Benefit Employees. Offering employees the option to cash out employer-paid parking subsidies avoids the seemingly intractable problem that voters don’t like new taxes and motorists don’t like to pay for parking they used to get free. Employers could continue to offer tax-exempt parking subsidies, so long as they broadened the offer. Cashing out adds a new alternative to the typical take-it-or-leave-it choice between a parking subsidy or nothing.

- Cashing Out Will Cost Employers Little or Nothing. Compared to other solutions to the employer-paid parking problem, the cash-option requirement is least intrusive in the employer’s decisions about employee compensation. The requirement is only that if an employer offers to subsidize commuting expenses, use of the subsidy cannot be confined to parking (and thus driving to work). The only added cost for an employer would occur in the unusual case of current ridesharers who are now offered the choice between free parking or nothing and yet do not take the parking. These current ridesharers would have to be offered the cash value of the parking subsidies they have not taken. But there can be only a very small percentage of employees who are now offered a parking subsidy but do not take it. The 1990 Nationwide Personal Transportation Survey found that 91 percent of the American work force commutes to work by car. And one reason that many of the remaining 9 percent do not commute by car is probably that they are among the few employees who are not offered employer-paid parking (and who therefore would not have to be offered the in-lieu cash). Of those very few who are now offered free parking but do not take it, some are already offered an alternative ridesharing subsidy (such as a bus pass), and for these employees the employer’s cost of the cash option would be the only difference (if any) between the cash option and the cost of the existing rideshare subsidy. Thus, the employers’ added cost of offering cash in lieu of parking subsidies would have to be inconsequential.

- Cashing Out Will Especially Benefit Low-Income and Disabled Employees. Because they are in the low tax bracket, the lowest paid workers would gain the most after-tax cash from a taxable tax allowance. Also, the cash allowance would be larger in proportion to a lower income, so the cash option would clearly improve the relative wellbeing of the lowest paid workers. Disabled employees and others who cannot drive a car will also benefit from the option to choose cash in lieu of a parking subsidy.

- Cashing Out Will Strengthen Central Business Districts. Employer-paid parking simply equalizes the cost of parking between downtown and suburban work sites (by making it free in both places) and does nothing to make downtown superior to a suburban location. Because downtown employers must pay more than suburban employers to provide employee parking, however, downtown employers could offer more cash in lieu of a parking space without any increase in their cost. This higher cash option for downtown employees would make downtown work sites relatively more attractive than suburban work sites, at least for those who rideshare. Downtown employees could more easily take advantage of the cash option by shifting to mass transit. Also, because a high density of employment implies a high density of potential fellow carpoolers, downtown employees could more easily shift to carpools. Finally, parking spaces vacated by new carpoolers would be a boon to visitors, including shoppers, business clients, and tourists.

- Cashing Out Will Yield a tax Revenue Windfall. In making the choice between a parking subsidy or its cash value, commuters would have to consider that the cash is taxable, while the parking subsidy is not. When a commuter does voluntarily choose taxable cash rather than a tax-exempt parking subsidy, federal and state income tax revenues increase. With very conservative assumptions, I have estimated that offering employees the option to cash out employer-paid parking subsidies would increase federal and state tax revenues by at least $1.2 billion a year. This increase in tax payments does not result from an increase in tax rates, or from taxation of previously tax-exempt parking subsidies. Rather, it results from voluntary action: cashing out an inefficient in-kind parking subsidy that costs the employer more to provide than the employee thinks it is worth. Put most simply, cashing out an inefficient parking subsidy converts economic waste into increased tax revenue and increased employee welfare, at no extra cost to the employer. This tax revenue windfall is an additional benefit above and beyond the reductions in air pollution, traffic congestion, and energy use.

The Reulsts of Cashing Out Employer-Paid Parking

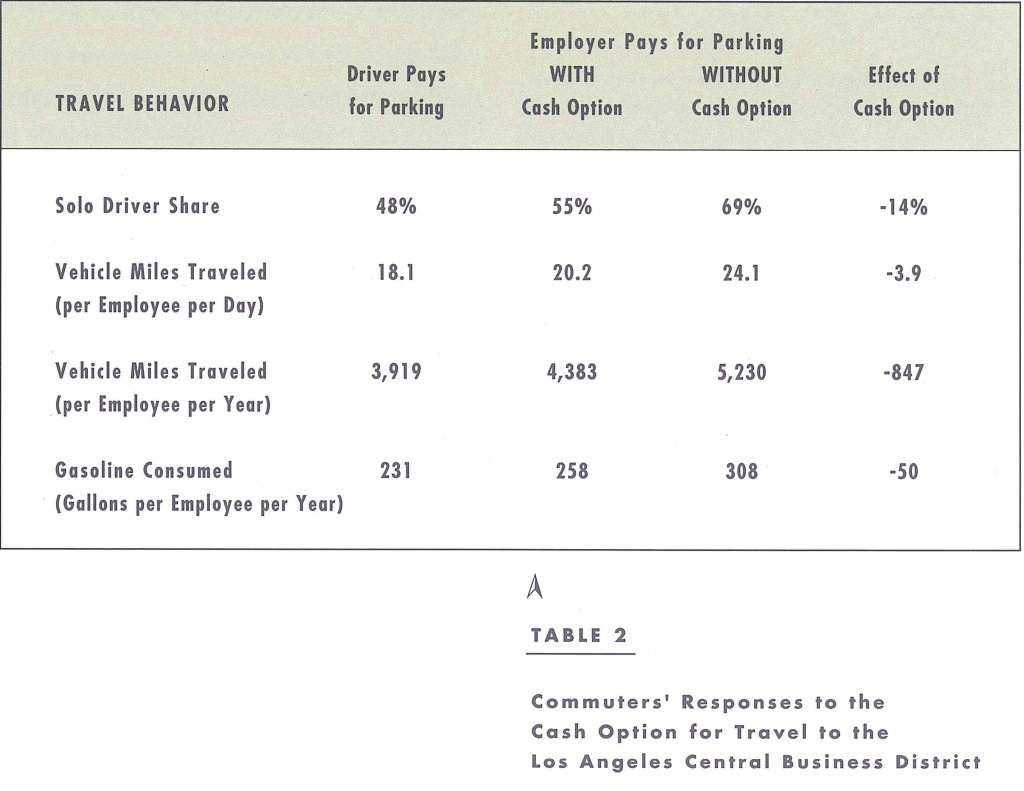

Table 2 shows estimates of how offering the option to cash out parking subsidies would affect commuters’ travel behavior. A mode-choice model was estimated with data from a survey of 5,000 commuters and their employers in down town Los Angeles. The model suggests that offering the option of a taxable cash travel allowance to employees who now park free in downtown Los Angeles would reduce their solo share from the current 69 percent to 55 percent. This mode shift would reduce automobile commuting by 84 7 VMT per commuter per year and would reduce gas consumption for automobile commuting by 50 gallons per commuter per year.

Although it’s risky to extrapolate from one city to the rest of the country, we can illustrate the implications of what has been found in Los Angeles. Approximately 90 million commuters park free at work in the United States. If all these commuters respond to the cash option as has been estimated for Los Angeles, automobile use for commuting would decrease by 76 billion VMT a year, and gasoline consumption would decrease by 4.5 billion gallons a year. Obviously, these estimates can suggest only general magnitudes and must be viewed cautiously.

Experience of Firms That Offer Their Employees the Cash Option

A survey of the few firms that already offer employees the cash option shows that it is simple and cheap to administer, particularly in comparison with other ridesharing incentives employers offer. A detailed case study shows how one firm was able to offer all its employees the option to cash out their parking subsidies without increasing the firm’s total cost of subsidizing.

California’s Parking New Cash-Out Legislation

The Federal Internal Revenue Code creates a strong incentive for employers to pay for their employees’ parking and thus a strong incentive for commuters to drive to work alone. States and localities are then left with the enormous problem of devising policies to deal with the resulting traffic congestion and air pollution. The State of California has recently enacted legislation (AB 2109) that directly addresses the problems caused by employer-paid parking and that serves as a model of how the Federal government could address the same problems. Briefly, the new California cash-out legislation requires employers of 50 or more persons who provide a parking subsidy to employees to:

provide a cash allowance to an employee equivalent to the parking subsidy that the employer would otherwise pay to provide the employee with a parking space. “Parking subsidy” means the difference between the out-of pocket amount paid by an employer on a regular basis in order to secure the availability of an employee parking space not owned by the employer and the price, if any, charged to an employee for the use of that space.

Note that the employer must offer an employee the option to take cash in lieu of a parking subsidy only if the employer makes an explicit cash payment to a third party to subsidize the employee’s parking. Therefore the employer clearly saves the cash paid for the parking subsidy if the employee takes the cash allowance instead. The employer’s avoided parking subsidy directly funds, dollar for dollar, the employee’s cash allowance, so there is no net cost for the employer when an employee forgoes the parking and takes the cash. The employer must offer the cash allowance only to each employee who is offered a parking subsidy. And each employee’s cash allowance is equal to the parking subsidy offered to that employee, so if some employees are offered smaller parking subsidies than other employees, their required cash allowance would also be smaller. Thus, the law is tightly written to avoid imposing a net cost on employers.

The California cash-out legislation also reduces the burden of parking requirements on new development by mandating that:

The city or county in which a commercial development will implement a parking cashout program … shall grant to that development an appropriate reduction in the parkingrequirements otherwise in effect for new commercial development.

Data derived from case studies and from a statistical model were used to estimate that cashing out employer-paid parking would reduce parking requirements for new development by at least 17 percent.

Implications for Federal Action

California’s cash-out legislation shows that it is feasible to require that employers who pay for parking if an employee drives to work must offer to pay the same amount if the employee rideshares to work. Some employers will undoubtedly encounter problems in adjusting to the cash-out requirement, but the new legislation will merely expose, not create, most of these problems. The real challenge for many employers will be to abandon the outdated notion that the best way to help employees get to work is to pay for their parking.

California’s experience suggests that, at the Federal level, it is sensible to proceed cautiously, beginning first with the requirement to offer cash in lieu of a parking subsidy only in the clearest “win-win” case where the employer pays out-of-pocket cash to a third party to subsidize employee parking. Later, after employers have been given sufficient advance notice to adjust to the emergence of a parking market where spaces are allocated by prices rather than by subsidies, the cash-out requirement could be extended to all employer-paid parking. To repeat, however, the proposed cash-out requirement does not prohibit, tax, or discourage any employer-paid parking subsidy. Rather, the proposal is simply that an employer who offers to pay for an employee’s parking if the employee drives to work must also offer to pay the same amount if the employee rideshares to work.

California’s experience suggests that, at the Federal level, it is sensible to proceed cautiously, beginning first with the requirement to offer cash in lieu of a parking subsidy only in the clearest “win-win” case where the employer pays out-of-pocket cash to a third party to subsidize employee parking. Later, after employers have been given sufficient advance notice to adjust to the emergence of a parking market where spaces are allocated by prices rather than by subsidies, the cash-out requirement could be extended to all employer-paid parking. To repeat, however, the proposed cash-out requirement does not prohibit, tax, or discourage any employer-paid parking subsidy. Rather, the proposal is simply that an employer who offers to pay for an employee’s parking if the employee drives to work must also offer to pay the same amount if the employee rideshares to work.

Because cash is taxable and a parking subsidy is tax-exempt, offering employees the option to cash out parking subsidies will reduce solo driving to work by less than would ending parking subsidies altogether. However, the research on commuters in Los Angeles suggests that the taxable nature of cash does not seriously diminish its attractiveness. Requiring employers to offer employees the option to cash out their parking subsidies will reduce traffic congestion, improve air quality, conserve gasoline, enhance employee welfare without adding to employers’ costs, and increase tax revenue without increasing tax rates. All these benefits will derive simply from subsidizing people, not parking.

References

Donald Shoup, Cashing Out Employer-Paid Parking, Publication No. FTA-CA-11-0035-92-1, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, 1 992. (This is the full 155-page report of the material summarized in this article. To request a free copy, write to Office of Technical Assistance and Safety, Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, 400 Seventh St., S.W., Washington, D.C. 20590.) UCTC No. 140

Donald Shoup and Don Pickrell, Free Parking as a Transportation Problem, Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, 1980.

Donald Shoup and Richard Willson, “Employer-Paid Parking: the Problem and Proposed Solutions,” Transportation Quarterly, Vol.46, No.2, April 1992, pp. 169-192. UCTC No. 119.

Richard Willson and Donald Shoup, “Parking Subsidies and Travel Choices: Assessing the Evidence,” Transportation, Vol. 17 ,1990, pp.141- 157. UCTC No. 34.