Many communities in the United Sates are taking a second look at the freeways built through and around their down- towns during the 1950s and 1960s. They see them now as barriers to neighborhoods and waterfronts. Several cities have removed stretches of urban freeways or have buried them. The city of San Francisco has taken down two elevated freeways and replaced them with surface streets. One of these new streets, Octavia Boulevard, opened in September 2005 as a multiway boulevard.

Multiway boulevards don’t get built very often in the United States, so when a new one emerges it is a notable event for the transportation and city planning professions. A multiway boulevard handles large amounts of relatively fast-moving through-traffic as well as slower local traffic within the same right-of-way but on separate but closely connected roadways. The street design is novel because it goes against prevailing standards, hence the question: how did Octavia Boulevard ever get built? The short answer is that it took a combination of committed and long-term citizen support, timely academic research, willingness on the part of public agencies to go against established norms, and a great deal of luck. The story of how Octavia Boulevard got built, and reflections on the final design, may be useful to professionals working in communities that are considering building a multiway boulevard.

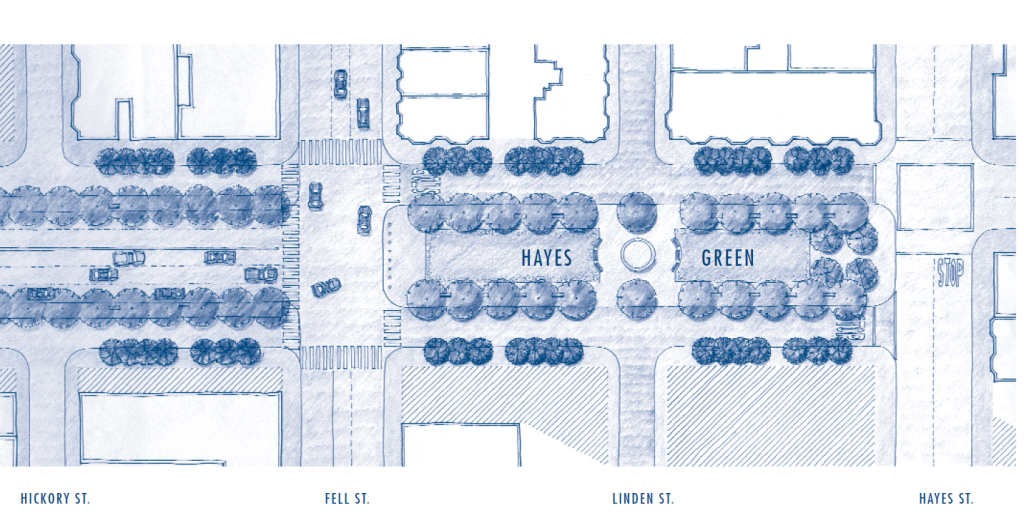

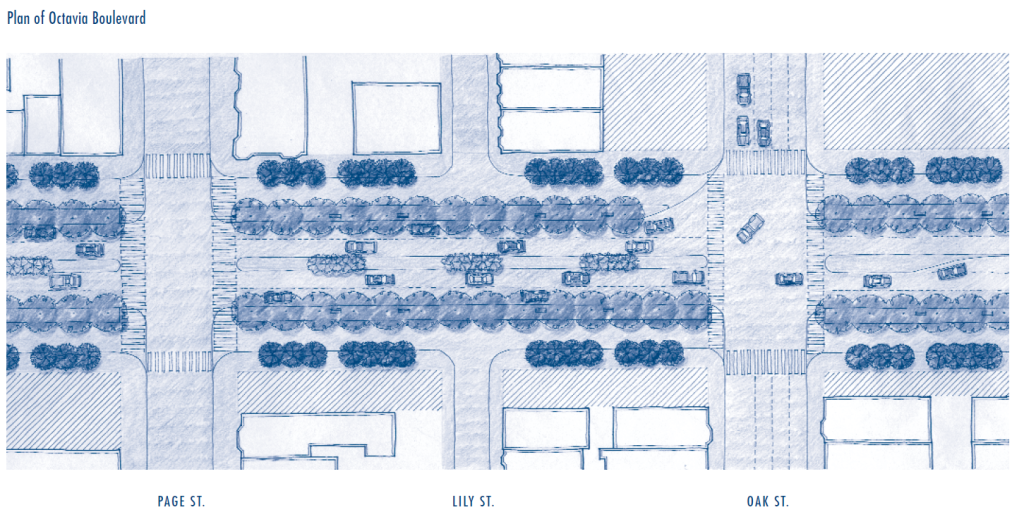

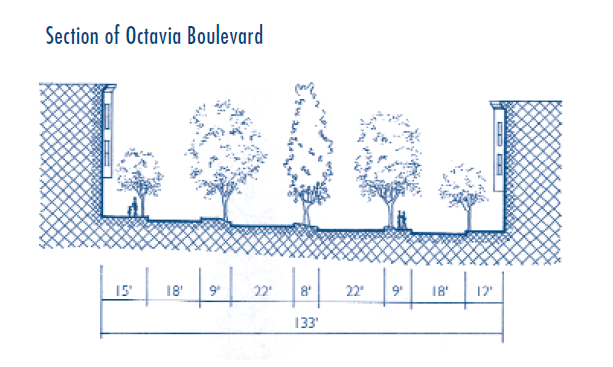

Octavia Boulevard is a four-block-long multiway boulevard crowned by a new park, Hayes Green, at its northern end. As with all classic multiway boulevards, it has central travel lanes for relatively fast-moving through-traffic bordered by tree-lined medians with walking paths. It has narrow one-way access roadways on each side for slower traffic and parking, and finally, at the edges, tree-lined sidewalks. The medians, narrow access roadways, and sidewalks together create extended pedestrian realms, where movement is at a slow pace.

Although modest in length, Octavia Boulevard is the first true multiway boulevard built in the United States since about the 1920s, with the exception of the Esplanade in Chico, California, which became a multiway boulevard upon removal of a railroad right-of-way in the 1950s. Octavia Boulevard replaces the double-decker elevated Central Freeway that was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

The Central Freeway

Built as part of San Francisco’s elaborate 1950s-era Trafficways Plan, the Central Freeway was intended to connect through to the Golden Gate  Bridge by way of Golden Gate Park. A citizen-led revolt in 1966 halted freeway construction through- out the city, but not before large sections had been constructed in Hayes Valley with devastating effects on the surrounding neighborhood. Put simply, the Central Freeway was not a nice place to live or do business near. But there it was for over thirty years, a short period as measured by the time-spans of freeways, a lifetime if you lived or worked in the neighborhood.

Bridge by way of Golden Gate Park. A citizen-led revolt in 1966 halted freeway construction through- out the city, but not before large sections had been constructed in Hayes Valley with devastating effects on the surrounding neighborhood. Put simply, the Central Freeway was not a nice place to live or do business near. But there it was for over thirty years, a short period as measured by the time-spans of freeways, a lifetime if you lived or worked in the neighborhood.

The 1989 earthquake did not topple the freeway but did severely damage it, raising the question of whether to retrofit or remove it. Amidst drawn-out and often heated community deliberations, a referendum to retrofit was put on the 1997 ballot, sponsored by residents potentially served by but not close to the freeway. It caught anti-freeway activists off-guard, and passed.

During the same time period but unrelated to the earthquake or the referendum, Allan Jacobs of the University of California, Berkeley published a book called Great Streets, which documented several classic multiway boulevards in Paris and Barcelona. Jacobs had been told by traffic engineers that such streets were dangerous because of their complex intersections with multiple roadways, but after spending time on them he began to question this assertion. People apparently adapted to the unusual street configuration, and traffic seemed to move easily and safely. Moreover, the streets were uniquely able to handle large volumes of through-traffic without imposing on the local environment. These observations led Jacobs, myself, and our colleague Yodan Rofé to undertake a two-year research project to test the safety of multiway boulevards and to understand their design qualities. Essentially, our research found that multiway boulevards are not more dangerous than normally configured streets carrying the same amount of traffic, if they are well designed.

Timing, as the saying goes, is everything. Hayes Valley citizen activists, tired beyond telling of the Central Freeway and conversant with Great Streets as well as the boulevards research, sponsored a measure that garnered enough support to be placed on the 1998 ballot, this time to replace the freeway with a surface multiway boulevard. It passed, overturning the previous ballot measure. The San Francisco County Transportation Authority, charged with implementing the boulevard, hired us to design it through our recently established firm Jacobs Macdonald: Cityworks.

Citizens protesting the Central Freeway in 1966 (left); it was demolished in 2003 (above). The new freeway ramp leading to Octavia Boulevard (right).

A Design Team

We knew that city staff would be unfamiliar with multiway boulevards and the design characteristics that make them work well and safely, and that close cooperation would be important. So we set up a process for working directly alongside city staff in the role of design leaders. It was important to have key city professionals at the table as the design progressed, for they were the people who would ultimately have to sign off on the design. The design team consisted of a planner from the Department of Parking and Traffic, two civil engineers and three landscape architects from the Department of Public Works, and three project managers from the Central Freeway Project office.

After introductory sessions aimed at bringing all participants up to date on the boulevard research and on examples of the world’s best boulevards, weekly meetings worked out increasingly detailed design proposals and then discussed, challenged, redesigned, and designed them again. The urban designers and engineers on the project team, naturally inclined in different directions on design questions, worked out an understanding that anticipated future open community meetings. They agreed that if there were more than one possible design solution to a functional question, and if both solutions could be acceptable even though the designers strongly favored one and the engineers another, they would all sign off on whichever the community chose.

After introductory sessions aimed at bringing all participants up to date on the boulevard research and on examples of the world’s best boulevards, weekly meetings worked out increasingly detailed design proposals and then discussed, challenged, redesigned, and designed them again. The urban designers and engineers on the project team, naturally inclined in different directions on design questions, worked out an understanding that anticipated future open community meetings. They agreed that if there were more than one possible design solution to a functional question, and if both solutions could be acceptable even though the designers strongly favored one and the engineers another, they would all sign off on whichever the community chose.

While the design progressed, presentations were made at regular intervals to an official Citizens Advisory Committee. The members were generally quite perceptive about what it would take to create a good boulevard and not just a traffic-moving corridor, and they were not afraid to take some gambles with the unknown. A major finding of the boulevards research had been “the elusiveness of wholeness,” meaning that focusing in turn on every potential traffic conflict or possible bad-driver behavior and trying to solve each by adding greater lane widths, wider turn radii, greater tree setbacks, or more movement restrictions was a misapprehension of the complex manner in which good boulevards work. Most committee members came to understand this, and a saying emerged: “No one gets everything; everyone gets a lot.”

Design Specifics

For the designers, a major consideration was to keep the boulevard as narrow as possible so that there would be room for new buildings along its eastern side, replacing structures torn down when the freeway was built. Having buildings facing onto the side access roadways was crucial for these spaces to make sense, whether the buildings were residential or commercial.

The widths of travel lanes arose as a major issue. The urban designers argued for narrow travel lanes, preferably ten feet or less, in order to  minimize the overall roadway width as well as pedestrian crossing distance, whereas the engineers argued for eleven- and twelve-foot-wide lanes. To achieve a narrow overall boulevard, the travel lanes, parking lanes, and side medians all needed to be as narrow as possible. Applying a standard interpretation of fire engine access rules to the side roadways would have resulted in very wide lanes. To solve this problem, the design team proposed placing the median trees near the central roadway and giving the access roadway side of the median a mountable curb. Thus, in the event of an emergency, a fire engine could easily enter the access road by driving with one wheel on the median. This design approach was vetted with the fire department and they agreed to it. In the end, lane-width compromises were reached all around, and the central lanes ended up eleven feet wide, the access lanes ten feet wide, and the parking lanes eight feet wide.

minimize the overall roadway width as well as pedestrian crossing distance, whereas the engineers argued for eleven- and twelve-foot-wide lanes. To achieve a narrow overall boulevard, the travel lanes, parking lanes, and side medians all needed to be as narrow as possible. Applying a standard interpretation of fire engine access rules to the side roadways would have resulted in very wide lanes. To solve this problem, the design team proposed placing the median trees near the central roadway and giving the access roadway side of the median a mountable curb. Thus, in the event of an emergency, a fire engine could easily enter the access road by driving with one wheel on the median. This design approach was vetted with the fire department and they agreed to it. In the end, lane-width compromises were reached all around, and the central lanes ended up eleven feet wide, the access lanes ten feet wide, and the parking lanes eight feet wide.

Another major design question was how to end the boulevard after Fell Street, where through-traffic turns west towards the Panhandle, and how to integrate it into the surrounding grid of narrower streets. Early suggestions by Caltrans included a one-block diagonal street with staggered building frontage, but a rather simple urban design solution was quickly agreed on and immediately embraced by the whole design team and the community. Between Fell and Hayes streets, the boulevard’s right-of-way would become a small neighborhood park, flanked by the access lanes.

This simple open space, dubbed Hayes Green, has proven enormously successful. Opened on World Environment Day in May 2005, it is constantly in use, particularly on weekends. For a designer, one can’t do better than hear comments like: “There are mothers who now have a place to take their young kids, where they meet and get to know other mothers and kids that they never knew about.” That, we suggest, makes for community.

Intersection issues were much debated, including how access roads would enter intersections, how intersections would be controlled, how close to intersections trees would be placed, and how wide to make the turning radii. Wanting to adhere as much as possible to existing street-design standards, the engineers on the team argued for returning the access roadways to the center prior to the intersections, holding trees back a considerable distance, and providing large turning radii. We argued for keeping the access roads straight so that they intersected independently with the cross-streets, for controlling the center roadway with signal lights and access roadways with stop signs, for carrying street trees all the way to the intersection, and for minimizing turning radii. Straight access roadways would allow local residents to stay among local, slow-moving traffic when driving.

Community Input

A preliminary design offered three alternative intersection approaches at three community-wide evening meetings: side access roads going straight through at intersections; side access roads returning to the center before intersections; and side access roads returning to the center both before and after inter- sections. Community response was lively.

One significant issue that the design team had not addressed emerged from these meetings: whether or not there should be separate lanes for bicycles. Separate lanes would have been wonderful, but an extra ten feet of width would have reduced developable land along the eastern side, in some blocks to no space at all. With no buildings facing onto the boulevard, the access roadways would have been pointless. We looked to the experience along the Esplanade in Chico, where bicyclists use the local access roads jointly with automobiles, with no resulting problem. The San Francisco Bicycle Coalition accepted this solution, but required assurances that bicyclists would be able to continue straight through at intersections without having to move into the central lanes. Along with arguments that local traffic should not be forced to enter the through-traffic flow at intersections, this issue convinced the community to choose the design alternative with straight-through side roadways.

To help decision-makers and the community visualize what Octavia Boulevard would be like, Peter Bosselmann of the UC Berkeley Simulation Laboratory built a physical model and made a video simulation of driving along the boulevard. This proved very helpful, and the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved the schematic design.

But, all was not done. In 1999, pro-freeway forces gathered enough signatures to compel a third referendum on retrofitting the freeway. Anti-freeway forces were by now better organized and were able to add a competing “Build Octavia Boulevard” measure to the ballot. San Francisco’s voters, presented with drawings of an already-designed multiway boulevard to compare to the still-standing freeway, voted for the boulevard.

It took the efforts of many people to get Octavia Boulevard built, but without a doubt local citizen activists really made the project happen. A group of concerned residents met continually, addressing problems and envisioning potential solutions even before the 1989 earthquake, and pushed for something better than they had. City bureaucrats were instrumental as well, particularly traffic professionals from the Departments of Parking and Traffic and Public Works. Each had to give a little and bend long- standing norms to help reach compromises. In the end, the Public Works Department prepared the construction drawings and saw Octavia Boulevard and Hayes Green through to completion.

Hayes Green looking North

Room for Improvement

Octavia Boulevard is not perfect. It contains compromises in design, construction, and regulation. Most apparent is that the local access roads are too wide—for a through-lane next to a parking lane, they were made eighteen feet wide, rather than 16.5 feet. A narrower space would have contributed more to traffic calming. Also, the surface of the local access roads was finished in asphalt, whereas it should be some material that marks them as part of a pedestrian realm, such as concrete like the sidewalks or cobbled pavers to match the medians. This was proposed during schematic design, but never made it into construction—and ought to be corrected. At Market Street, the entry into the eastern side access road should be narrower and less inviting to discourage through-traffic from entering it.

Operationally, there are intersection control confusions because conservative regulators were not willing to experiment or give people a chance to adapt. The side lanes ought to be controlled by stop signs and the central lanes by traffic signals. Concern over this unusual arrangement (which has been shown to work just fine on Chico’s Esplanade) prompted the installation of flashing red lights at the access road intersections, which drivers have difficulty interpreting.

Finally, the transition from the freeway to the new boulevard is less than successful. What’s left of the elevated freeway now touches down just south of Market Street. During the design process we were very concerned about making sure that this threshold clearly signaled to drivers that they were now on an urban street where different driving behavior was necessary. Although meetings were held with Caltrans engineers to find a solution for what the designers called “touch down” problems, some were never solved satisfactorily. Issues include too-wide ramp lane widths, turns allowed onto Market Street, and no appropriate signage or other cues to reduce vehicle speed, such as a roughened surface texture on the ramp.

Lessons from Octavia Boulevard for building future multiway boulevards, we suspect, will emerge over time. Currently, the street is too newly arrived to say anything conclusive. Nonetheless, the process of  coming to a final design suggests the following:

coming to a final design suggests the following:

Research like that carried out on boulevards can be very effective in bringing about change—if focused on specific street types, directed to professionals, and presented clearly in narrative and graphic form so that citizens as well as urban design professionals can easily make sense of it.

The design process is important. The right people must be sitting around the table on a regular basis. Problems and constraints must be raised and solutions agreed to during schematic design, not after a design is prepared and presented. This includes design sign-off by all interested parties.

Finally, citizen participation and advocacy may not be everything, but it is extremely important in terms of getting inherently conservative city governments and bureaucracies to consider and eventually implement an innovative street design. When one considers all that the citizens brought to the table—referenda, political activism, willingness to keep learning, advocating, and discussing over many years, unwillingness to give up, personal funds—one cannot escape the conclusion that their efforts are a main reason that Octavia Boulevard exists.

Further Readings

Peter Bosselmann and Elizabeth Macdonald, “Livable Streets Revisited,” Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 65, no. 2, 1999.

Allan Jacobs. Great Streets (MIT Press, 1993).

Allan Jacobs, Elizabeth Macdonald, and Yodan Rofé. The Boulevard Book: History, Evolution, Design of Multi-Way Boulevards (MIT Press, 2002).

Allan Jacobs, Yodan Rofé, and Elizabeth Macdonald, “Multiple Roadway Boulevards: Case Studies, Designs, Design Guidelines,” Working Paper No. 652, University of California, Berkeley: Institute of Urban and Regional Development, 1995.

Allan Jacobs, Yodan Rofé, and Elizabeth Macdonald, “Boulevards: A Study of Safety, Behavior, and Usefulness,” Working Paper no. 625, University of California, Berkeley: Institute of Urban and Regional Development, 1994.

Elizabeth Macdonald, “Structuring a Landscape/Structuring a Sense of Place: The Enduring Complexity of Olmsted and Vaux’s Brooklyn Parkways,” Journal of Urban Design, vol. 7, no. 2, 2002.